Why China’s Consumer Development is Assured

Lewisian turning point impacts upon China demographics with India close behind, meaning sales opportunities in China exist as never before

Op-Ed Commentary: Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Mar. 27 – China is about to become a great market for international businesses to sell to. That’s quite a statement, and I can recall similar proclamations being bandied about 20 years ago during the early days of Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, and then 10 years later when China eventually joined the WTO. Yet, as many a wise man noted – unless you were in the chopstick business, there weren’t actually a whole bunch of affluent Chinese looking to buy goods and services. That is now changing. But why?

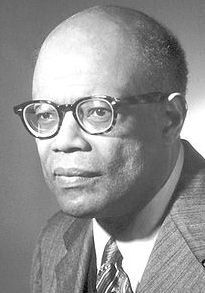

Sir William Arthur Lewis, Nobel Prize for Economics, 1979.

Let me introduce you to Arthur Lewis. Lewis was an American economist, born in 1915, who won a Nobel Prize in his field in 1979. One of his theories, now known as the “Lewisian turning point,” was written in 1954 and titled “Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labor.” In it, he lays out the economic principles that a “capitalist” sector develops by taking labor from a non-capitalist backward “subsistence” sector. At an early stage of development, there would be an “unlimited” supply of labor available from the subsistence economy which means that the capitalist sector can expand without the need to raise wages. This results in higher returns to capital which are then reinvested in further capital accumulation. In turn, the increase in the capital stock leads the “capitalists” to expand employment by drawing further labor from the subsistence sector. Given the assumptions of the model (for example, that the profits are reinvested and that capital accumulation does not substitute for skilled labor in production), the process becomes self-sustaining and leads to modernization and economic development.

The point at which the excess labor in the subsistence sector is fully absorbed into the modern sector, and where further capital accumulation begins to increase wages, is called the “Lewisian turning point.” This is the point that China has reached now.

China’s own development has mirrored the scenario predicted by Lewis and the result has been a shift in China from 20 years ago, when it had a large, young and available workforce with an average age of 23, to today’s more mature workforce with an average age of 37. Back some 20 years ago, the typical male worker may have been interested in having a couple of beers, smoking a few cigarettes and chasing girls. Today, he is married, has a child, a mortgage and both sets of parents as dependents. Simply put – today’s worker in China needs to have money in his pocket.

This is borne out by China’s government reacting to this shift by steadily increasing salaries, increasing welfare payments, and ensuring that he can afford to support the rest of his family. In short, China is developing a middle class. Estimates vary, but this is generally reckoned to be between 200 million and 250 million with middle class income to Chinese standards. When holding middle class income to U.S. standards, this figure is reduced to a lower, yet still impressive, 80 million.

What’s more impressive, however, is that the middle class is set to grow dramatically – McKinsey estimates that this figure will double by 2020. This means that the days of “cheap China” – when the world went to the country to manufacture cheap goods and sell elsewhere – are coming to a close. In its place has emerged a wealthy middle class of consumers, now both willing, able and financially secure enough to buy goods and services. If there was ever a time to reassess the China market as a viable destination for international businesses to sell to, that time is now.

But what about that cheap manufacturing? Conveniently, the average age of a worker in India today is the same as that in China 20 years ago: 23. The only difference between China then and India today is that India starts it’s ascent towards the “Lewisian turning point” with an existing middle class of 200 million to 250 million – curiously the same as China’s today.

The next two decades will see China emerge as a significant consumer market, and the impact of this is just beginning to be realized. To get into that, foreign companies need to act now to get in ahead of the competition. I already outlined the initial strategic steps – trademark registration – in yesterday’s article. We will also see a shift in India. Globally inexpensive products labeled “Made in China” will shift to “Made in India,” and Washington will soon complain about the Indian-American trade imbalance, and probably also have concerns over the U.S dollar-rupee exchange rate. All this will come to pass – the demographics, population, and economic theories all point to it being so.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the founding partner of Dezan Shira & Associates. Founded in 1992, the practice assists foreign companies establish operations in China, India and Vietnam, and maintains 20 offices throughout the region. Please email asia@dezshira.com for assistance in these markets or visit the practice’s website at www.dezshira.com.

Related Reading

The End of Cheap China by Shaun Rein

The End of Cheap China by Shaun Rein

A fascinating and recommended account of China’s shifting demographics and what this means – just released and available on Amazon.

Doing Business in China

Doing Business in China

Our 156-page definitive guide to the fastest growing economy in the world, providing a thorough and in-depth analysis of China, its history, key demographics and overviews of the major cities, provinces and autonomous regions highlighting business opportunities and infrastructure in place in each region. A comprehensive guide to investing in the country is also included with information on FDI trends, business establishment procedures, economic zone information, and labor and tax considerations.

Selling to China & India’s Middle Classes – A Vietnam Manufacturing Play?

FICE Franchising in China: A Flourishing Business Model

India and China’s Retail Industries Compared

China’s Provincial Retail Statistics for 2011

- Previous Article Planning Your Trademark Strategy for China

- Next Article Average Wages and Social Security Caps for Cities across China