China’s Civil Code: Implications for E-Commerce Firms

China’s Civil Code amalgamates legal provisions and judicial interpretations that will affect various personal and property rights, with clear implications for the regulation of the e-commerce industry as well.

By Donfil Huang, Dezan Shira & Associates’ Guangzhou Office

On May 28, 2020, the PRC Civil Code was enacted and released to the public. The Civil Code comprehensively stipulates various personal and property rights and interests closely related to citizens’ daily life.

In this article we briefly introduce the Code and its specific implications for the e-commerce industry in China.

What is the Civil Code?

To understand legal provisions regarding various personal and property rights and interests in PR China, such as property entitlement after marriage, or what you should pay attention to when renting a new apartment, or compensation claims you can make if your neighbor’s apartment leaking water and has damaged your ceiling – you would have to look up some of the following People’s Republic of China laws – Marriage Law, Contract Law, Real Right Law, and Tort Law etc.

However, from January 1, 2021, all of these provisions will come under a unified civil code instead.

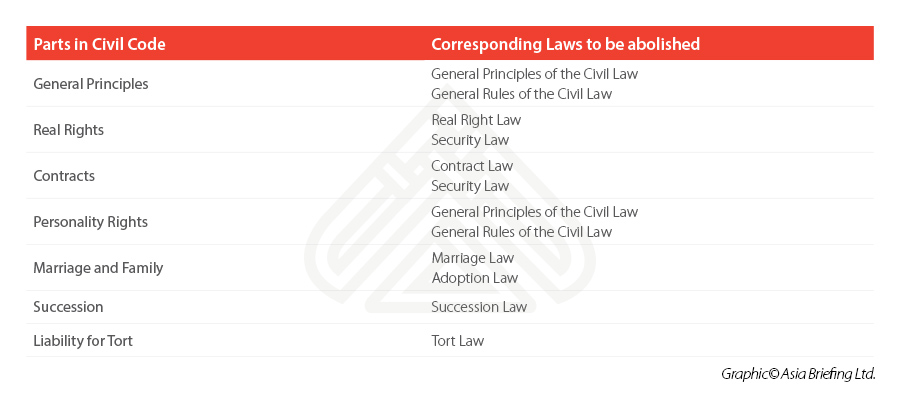

The PRC Civil Code has a total of 1,260 articles and comprises of seven Parts (see table below) and the Supplementary Provisions. Among the 1,260 articles, only around 148 articles are newly added, the others are amended or rephrased based on the existing laws and judicial interpretation, or directly copied from there. Therefore, after taking effect on January 1, 2021, the corresponding laws of the related parts (see table below) will be abolished simultaneously.

What are the implications for e-commerce?

‘E-commerce’ refers to business activities of sale of goods or provision of services through the Internet and other information networks. It includes a range of service transactions, from ordering food, buying clothes and bags, to ordering door-to-door house cleaning services via apps; investing your money in finance products via P2P platforms, etc.

The following terms are key to understanding what types of businesses and business operations will be impacted by the legal provisions relating to e-commerce in the PRC Civil Code.

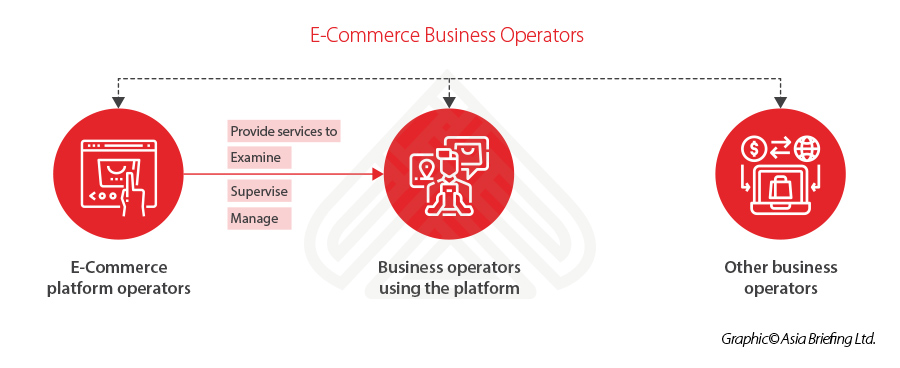

- E-commerce business operators: Consists of e-commerce platform operators, business operators using the platform, and other e-commerce business operators.

- E-commerce platform operators: Refers to legal persons or non-legal-person organizations who provide online business premises, transaction matching, information dissemination services, etc. for both parties or multiple parties in e-commerce transactions to facilitate both or multiple parties in carrying out transaction activities independently.

- Business operators using e-commerce platforms: Refers to operators selling goods or providing services through an e-commerce platform.

- Other affected business operators: Refer to operators selling goods or providing services through their self-built website or other network services other than an e-commerce platform.

How does the Civil Code apply to e-commerce in China? Some FAQs

1. Do we have ‘contracts’ in e-commerce? Since when am I legally bound and protected?

In traditional understanding and practice, a contract is visible and tangible, concluding the aligned details between the involved parties with regards to a subject matter, and properly confirmed by the parties, for example, by signing or affixing with stamps. For instance, when you rent an apartment, you print and sign a lease agreement with your landlord in duplicate and each party holds one copy. In e-commerce, you just drag the goods you prefer into the shopping bag and pay and wait for its arrival. It seems like you never signed any contract.

The fact is you have contracts in place, and you are protected by them.

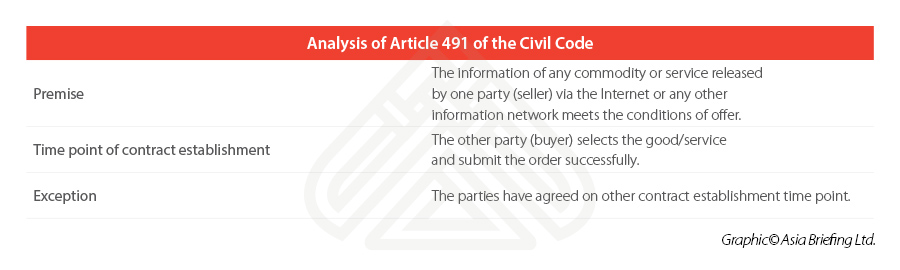

Contracts are recognized by law in various forms: in writing, in oral form, and in some cases – maybe even by actions, etc. The form of contract “in writing” is further interpreted as by letter, telegram, telex, or fax, etc. In particular, the Civil Code clearly acknowledges that the accessible electronic data is regarded as information “in writing” (Article 469).

Most activities in e-commerce are electronic data exchange activities, as the information is processed through the generation of electronic data. That is to say, the price, the discount, the description of a product in text or/and pictures as shown on its sale page, and the promise of delivery days, the promise of return without cause as posted on the page or communicated by the seller (or its agent or representative) via personal chat on the e-commerce platform, are information and communication in writing and such information and communication, when proper and applicable, form part or full form of the contract between the buyer and the seller.

So, when does a contract become effective and binding? The Civil Code has an explicit answer, as shown in the table below.

Therefore, imagine you ordered your lunch via an app but your dish never arrived – you do not need to worry as you are protected by a contract or more than one contract (for example, the contract between you and the restaurant and the one between you and the platform) at the time when you placed the order. You have the rights to, at least, get the lunch fee refunded, and if the platform/ restaurant has also promised additional compensation due to late arrival, you can get such compensation as well.

2. What is regarded as “delivery”?

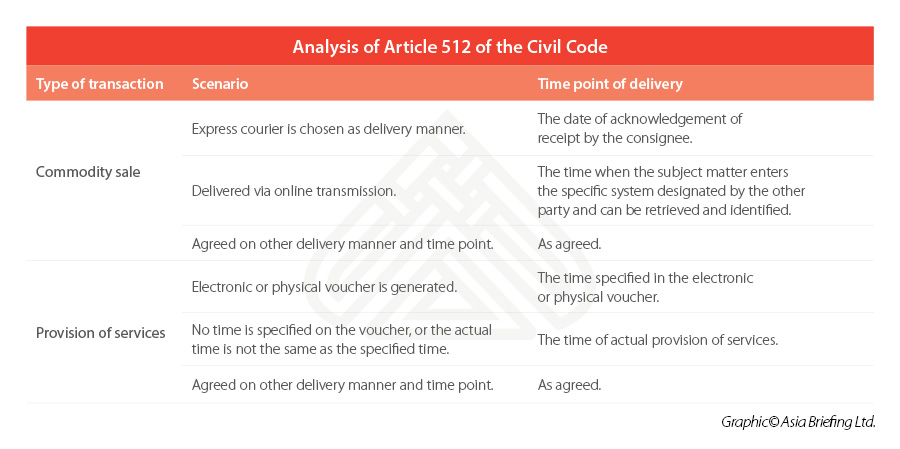

When dealing with e-commerce businesses, the delivery of the goods/services is one of the more crucial concerns between the involved parties – the time of delivery is a key point to split or determine the rights, responsibilities, and risks of each party.

The apparent improvement in the Civil Code is that it has explicitly set out the provisions about delivery in e-commerce, while the Contract Law had no specific provision in this regard.

3. Is my personal data protected in e-commerce?

Unlike other enterprises, which may have a limited need to gather personal data, e-commerce operators are required to access and use massive personal data and even sensitive personal data. For instance, if you use a take-away food service app, you must input your personal address (to deliver the food to your person) and personal phone number (to contact you when needed). Other details may also be gathered, such as date of birth to trigger discounts or provide more information to tailor the app’s algorithm to cater to your tastes more efficiently. An e-store selling clothes will ask not only your address and phone number, but also your gender, height, weight, age, etc. The online drug store will even know the physical health status of the buyers. In practice, e-commerce activities not only involve your personal data, but also, more importantly, your privacy.

Take a recent case, where a courier company tried delivering a document to a lady’s home address but found she was not at home at that moment. The courier company searched its database and found the lady’s “office address”, then delivered the document to the office where she worked. However, the delivered document itself was from another employer of the lady, which was thus disclosed to the current employer. The lady was dismissed by the employer for working for two companies at the same time. To compensate for this loss, the lady sued the courier company with the cause of infringement of her right to privacy. The court supported the lady’s claim and judged that the courier company shall compensate the lady with RMB 10,000 (approx. US$1,480).

One of the advantages of the Civil Code is that it not only reiterates people’s right to their personal data, but also for the first time, stipulates the right to privacy in detail. Though previous and current laws have mentioned “privacy” and acknowledge the “right to privacy”, the Civil Code is the first such codified law that formally defines what is “privacy”. It further stipulates detailed articles listing what are the forbidden types of behavior that may infringe on people’s privacy.

The table below illustrates what the PRC Civil Code defines as personal data and privacy.

Therefore, your personal data (as well as your privacy) will be protected not only in the course of engaging in e-commerce activity, but also in other daily activities, particularly after the Civil Code comes into effect.

General regulation of e-commerce in China – FAQs

While the Civil Code is a comprehensive code regulating quite a lot of matters with regards to civil relations, it does not regulate all aspects of any specific matter.

For e-commerce as well, there are various laws and regulations, in addition to the Civil Code, that stipulate further and deeper legal provisions to regulate this area of activity.

1. What if I were a foreign investor aiming to invest in e-commerce in China?

Since June 19, 2015, e-commerce in China has been opened to 100 percent foreign direct investment (Circular of Ministry of Industry and Information Technology concerning Lifting Restrictions on the Proportion of Foreign Equity in On-line Data Processing and Transaction Processing Business (for-profit e-commerce), MIIT [2015] No. 196).

In other words, since 2015, foreign-invested enterprises (“FIE”) that are also wholly foreign-owned are allowed to do e-commerce business in China.

In contrast to the part of the Civil Code that regulates the relations between equal individuals or/and legal entities, which is regarded as “private law”, the regulations regarding foreign investment are “public law”, which regulates the relations between governmental organs and their counterparts. Such “public laws”, include but are not limited to the Administrative Provisions on Foreign-funded Telecommunications Enterprises, Administrative Measures on Internet-Based Information Services. They stipulate certain requirements for FIEs operating in e-commerce, as briefly explained below:

- The primary foreign investor of the FIE shall have a good track record and operational experience in such area.

- The minimum registered capital of the FIE operating e-commerce nationwide or across provinces shall be RMB 10 million (US$1,479,925). (US$1=RMB 6.76).

- The minimum registered capital of FIE operating e-commerce within a provincial level territory shall be RMB 1 million (US$147,992).

- If the e-commerce activities relate to press, publishing, education, healthcare, pharmaceuticals, and medical instruments, the FIE shall also obtain approval from other relevant governmental authorities.

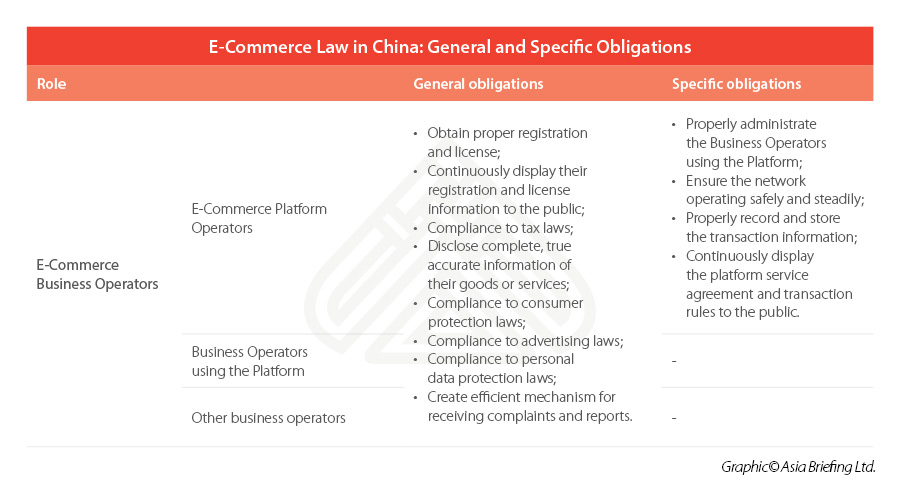

2. What general obligations do I have when I am doing business in e-commerce in China?

The E-Commerce Law is more specific and detailed on the area of e-commerce than the Civil Code.

For different roles as mentioned in preceding paragraphs, the E-Commerce Law has provisions about their respective obligations, as briefly stated in the table below.

Apparently, as e-commerce platform operators, the obligations of firms are heavier than is the case with other e-commerce business operators. Using the metaphor of a shopping mall, the business operators using the platform are like individual shop operators who may merely focus on their own transactions and compliance, whereas the e-commerce platform operator is similar to the shopping mall operator who must not only care for its own business but must also keep a close eye on all the shops to make sure they are doing business properly.

3. What are other areas that e-commerce entities must pay attention to?

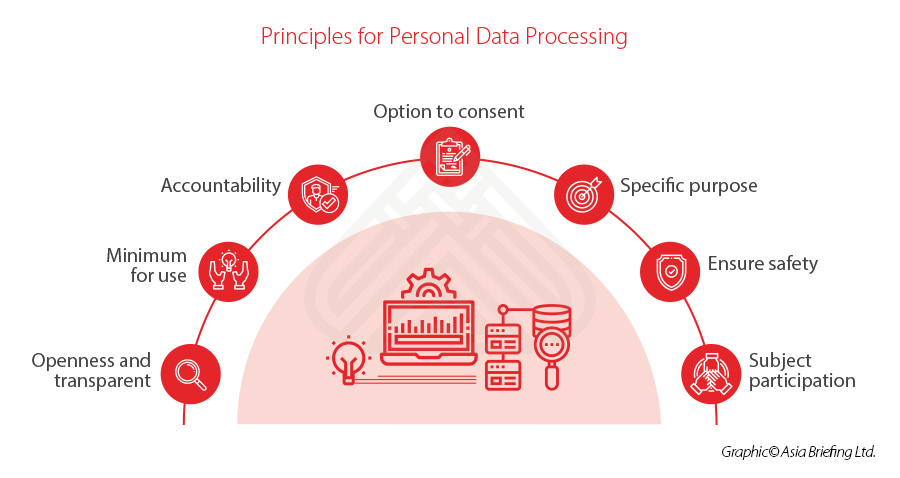

E-commerce activities trigger multiple aspects of legal relations, and thus cannot be completely regulated by only one law. The PRC Civil Code regulates partial matters that are generally applicable to e-commerce; for example, contracts, right to privacy, and rights to protection of personal data. The E-Commerce Law mainly illustrates the requirements for and obligations of e-commerce business operators. Other specific laws, for example, the Cybersecurity Law and the series of statutory standards for personal data protection – set out specific and even technical requirements – constituting critical parts of the regulatory system governing e-commerce activities in China.

As we learned from above, how to collect and use personal data reasonably and legally is very important for e-commerce business operators in their daily business activities. Any negligence or non-compliance can lead to huge damage to their business and reputation.

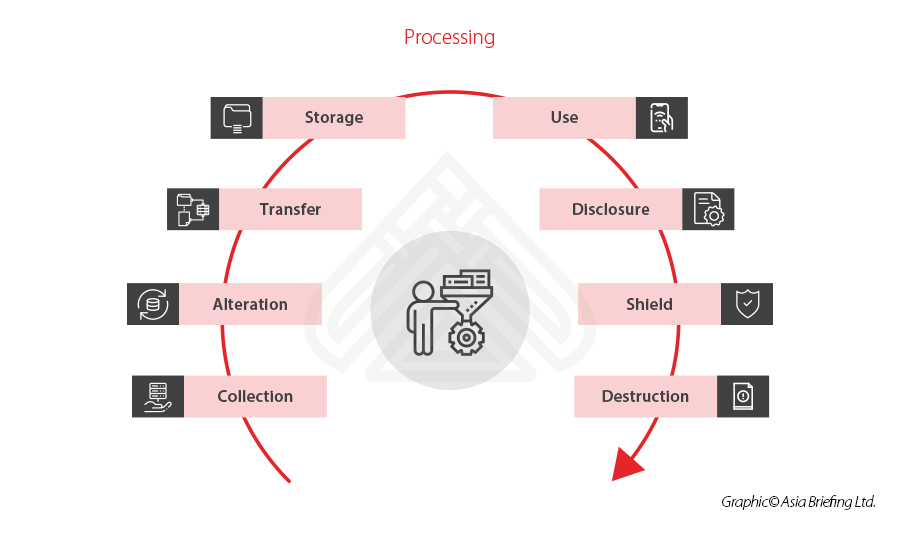

Personal data protection is a deep and comprehensive topic and requires a separate article on this topic. In a nutshell, the entities that control or/and process personal data, are required to adhere to certain principles during the whole cycle of processing personal data.

Conclusion

To recap, the Civil Code has formally and clearly confirmed (again) the unique form of contracts (via exchange of electronic data) in e-commerce. This will both facilitate the development of e-commerce in China while also confirming the existence and protection of people’s right to privacy and their personal data.

While the Civil Code itself has a comprehensive scope, it does not and cannot regulate every aspect of specific matters. When studying the regulatory system as applicable to a specific industry or business activity in China, multiple laws will need to be examined to have an overall understanding of the compliance expectations as well as rights and obligations.

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

We also maintain offices assisting foreign investors in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, United States, and Italy, in addition to our practices in India and Russia and our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative.

- Previous Article Was ist der China Standards 2035 Plan und wie wird er sich auf aufstrebende Industrien auswirken?

- Next Article What does the Yangtze River Delta Integration Mean for Businesses in China?