Explainer: What’s Going on in China’s Property Market?

China’s property market plays an outsized role in the global economy. It is intricately linked to core industries, performance of local governments, besides investors and homeowners. 2021 data showed that China’s largest property developers have accrued trillions of dollars in debt, causing alarm among economists and investors alike over fears of financial instability. While the Chinese government ended the year by easing restrictions on debt refinancing and loans, it is as yet unclear if this will be enough to reverse course in 2022.

2021 was an annus horribilis for China’s property market. The real estate sector had been riding a wave of optimism on the back of record sales in 2020 but ended 2021 with some of its largest players defaulting on billions of dollars debt and plummeting sales numbers.

Though the events that unfolded in 2021 came as a surprise to many industry insiders, they were nonetheless a culmination of long-standing issues, ranging from mounting debt to unsustainable growth strategies. That volatility was suddenly exposed when a 2020 rule for property developer financing began to stress liquidity.

Trouble in the property sector could spell trouble for China’s economy as a whole. Some analysts are concerned that drops in housing sales and curbs on lending will have a negative impact on economic growth in 2022. The health of the real estate market has a direct spillover effect on affiliate industries and ultimately, property owners.

In this article, we take a bird’s eye view of China’s property market, note key stakeholders that include local governments and the financial industry, and finally, trace the events leading up to the sector’s ongoing crisis. We also cover steps taken by the Chinese government to steer the property market towards stability and wrap up our analysis with what to expect in 2022.

Background: China’s property market and the economy

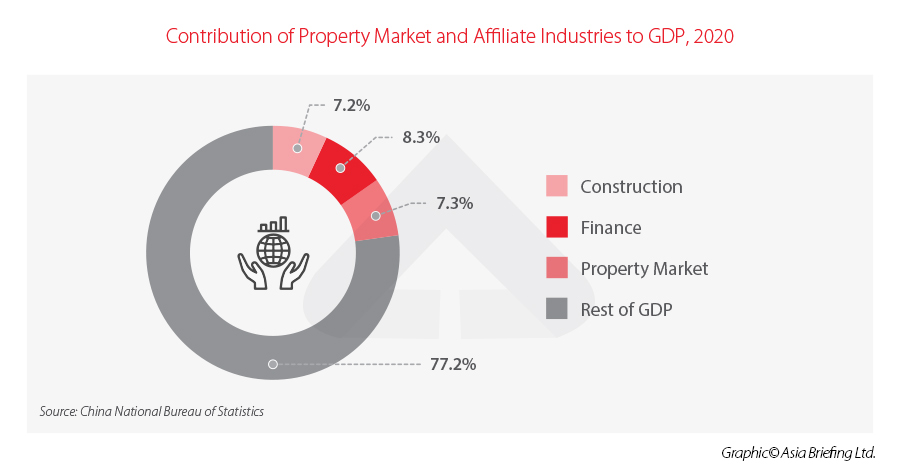

China’s property market has been a key driver of the economy ever since the country began opening its markets in the 1980s. Today, the property market is still a major contributor to the economy, with estimates ranging from 17 to 29 percent of GDP, depending on the scope of industries included.

According to the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), direct investment in real estate in 2020 reached about RMB 7.5 trillion (US$1.18 trillion), a contribution of about 7.4 percent to GDP. Data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) show that the construction industry, which is predicated on real estate, contributed a further RMB 7.3 trillion (US$1.15 trillion), or 7.2 percent of that year’s GDP.

In terms of investment, in 2020, 51.5 percent of investment in fixed assets nationwide was driven by real estate, of which investment in real estate development accounted for 27.3 percent, according to Ren Zeping, chief economist at Soochow Securities, a financial services institute (link in Chinese).

Although not among China’s main employers, a huge number of jobs are reliant on the health of the property market. Construction and financial industries are large employers and hugely dependent on the health of the real estate sector. Employment in the construction sector peaked in 2020 when it recorded over 62 million jobs.

The number of people whose livelihoods are dependent on the real estate sector expands even further when including industries that are contingent on property holdings, ownership, and distribution, such as wholesale and retail.

Key players and stakeholders in China’s property market

The property market plays an outsized role in China’s economy, as can be seen from the economic data presented above. Its position in the economy is further complicated by the way it engages with various areas of society, from homeowners to local governments.

Below we look at the main stakeholders in China’s property market.

1. Homeowners and prospective homeowners

China has one of the world’s largest rates of homeownership, which reached 90 percent in 2020.

This is in large part due to the fact that property is seen as a source of economic stability and security. There is also a cultural element to this phenomenon, as owning a home is traditionally seen as a prerequisite for marriage, particularly for men. For this reason, families and friends will pool together money to buy a house for their children to help them with marriage and family prospects.

The cultural factor, however, is often overstated, especially when considering that homeownership is an important middle-class marker in many parts of the world. It is also clear that buying a home – and even a second or third home – has increasingly come to be seen as a savvy financial investment, which we discuss in more detail below.

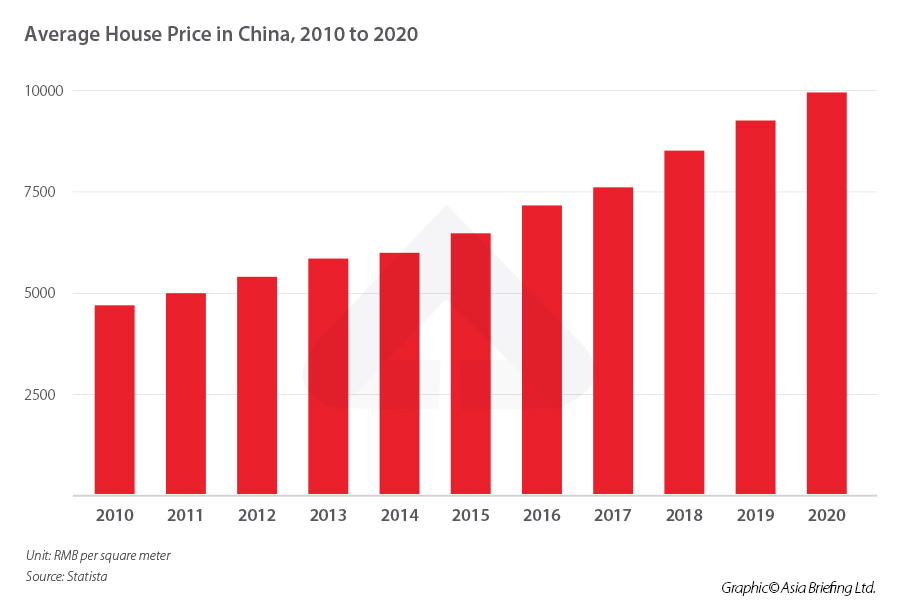

This demand has driven home prices up over the last two decades, culminating in a nationwide average of almost RMB 10,000 (US$1,571) per square meter in 2020.

This issue is exacerbated by a high demand for housing, particularly in large metropolises where housing shortages compounded with rising demand have served to push house prices even higher. Shanghai and Shenzhen, for example, recorded average house prices per square meter of RMB 66,801 (US$10,526) and RMB 71,209 (US$11,221), respectively, at the end of 2021.

Moreover, housing shortages are not being experienced everywhere in China. Many smaller cities and rural areas have housing surpluses as people moving to larger cities have left many new – and sometimes speculative – developments / allotments empty.

Property as an investment

A huge proportion of personal assets are tied up in the property sector in China – as much as 70 percent of household wealth is in property.

The constant rise in house prices also means that property has over the years increasingly come to be seen as a lucrative investment. This is compounded by the fact that China currently doesn’t have a property tax (more on this later), which further facilitates more families and individuals to buy second or even third homes in the expectation that prices will continue to rise.

This has happened in tandem with a rise in property presales, wherein a property developer sells a home to an individual or investor that does not yet exist. This is where the intersection between finance and the property market becomes particularly strong, and where the beginning of China’s property woes can be seen.

2. Property developers

Property developers are some of the largest companies in China. These companies made huge profits off the back of the property boom that China has seen over the past two decades. According to data from the NBS, total sales of commercial housing grew from RMB 5.8 trillion (US$914 billion) in 2011 to RMB 17.3 trillion (US$2.7 trillion) in 2020, a 21.8 percent annual growth rate.

Residential housing makes up the lion’s share of the new builds by property developers. Combined, property developers built 16.4 trillion square meters of new residential housing in 2020, accounting for approximately 73 percent of total new builds.

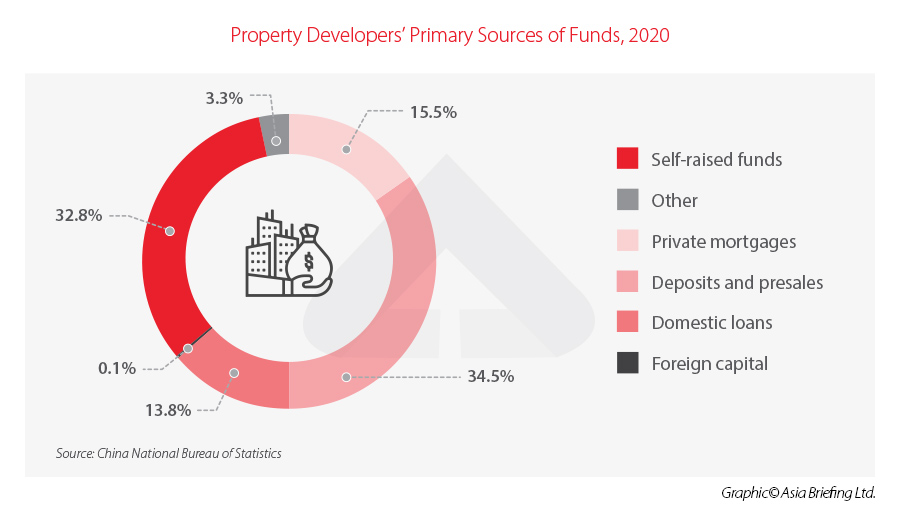

The largest source of income for property developers in 2020 (the latest available data) were deposits and presales, indicating a huge reliance on so-called ‘speculative’ spending from individuals and enterprises. That year, property developers raised over RMB 6.6 trillion (US$1 trillion) from these two sources alone.

Property developers are also highly reliant on credit to enable the liquidity needed for their projects. In 2020, the property development sector took out a total of RMB 2.6 trillion (US$419 billion) in domestic loans.

These loans have built up over the years, and as of June 2021, the property development sector had accumulated RMB 33.5 trillion (US$5.2 trillion) in debt, according to Nomura, a financial services company (as reported by Reuters).

This build-up of debt has been a major concern for the government for a number of years and led to the introduction of the ‘three red lines’ policy in August 2020, which aimed to curb lending by big developers. We discuss this policy and its impact in more detail below.

3. Banks and financial institutes

As has been mentioned above, a substantial portion of funding for property developers comes from bank loans. This means that the property market is also inextricably linked to the financial industry. While this is also a global phenomenon, it is particularly true in China, where real estate loans accounted for 27.4 percent of total loans issued in 2020.

Many of the banks exposed to the real estate industry are also some of China’s largest state-owned enterprises and include the likes of China Construction Bank, CITIC Bank, and Bank of China. This places the banking industry at major risk from volatility in the real estate industry, and concerns over the potential financial contagion from debt defaults abound.

According to Bloomberg, the number of loans issued to real estate developers fell significantly in the second and third quarters of 2021, down RMB 120 billion and RMB 140 billion, respectively. In addition, according to S&P Global Ratings, the non-performing loan ratio of property loans – that is, the ratio of outstanding property loans that are seeing no payments – may have risen to 5.5 percent at the end of 2021, up from two percent in 2020.

However, defaults by property developers in late 2021 and 2022 have yet to lead to significant financial instability in the country, leading some to believe concerns are overblown.

4. Local governments and financing vehicles

To fully understand China’s property market, we must also understand the relationship it has with the government, and local governments, in particular.

In China, the government owns the rights to all land in cities. Companies and individuals can purchase land-use rights from the government for a period of up to 70 years, after which time the lease can be extended. The property built upon the leased land can be bought and owned by companies and individuals.

Land sales are therefore a major source of income for the government, especially local governments. This reliance on land sales is compounded by the fact that local governments are responsible for spending on public infrastructure in their jurisdictions as a means of stimulating the economy and ensuring jobs.

In addition, local governments had been prohibited from raising money through bond sales until 2015. For this reason, land sales have been a major lifeline for local governments. It is estimated that revenue from land transfers and real estate special tax together accounted for 37.6 percent of local governments’ fiscal revenue in 2020.

And just as local governments rely on real estate developers to lease land to raise funds, so property developers rely on local governments to fund development. As mentioned, local governments are responsible for a large proportion of infrastructure spending in their jurisdictions, which means they are frequently the main contractors for the developers, and by extension, construction companies.

Though land sales have helped to fund some of these projects, to sustain the high levels of spending required to drive economic growth, local governments have also had to turn to other sources of liquidity. This is where the use of local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) comes in.

LGFVs are investment companies that are owned by local governments. They were created as means to bypass a ban on direct borrowing by governments. The LGFV can take out loans on behalf of the government to finance infrastructure or welfare projects.

In addition to bypassing the ban on direct borrowing, debt accrued by LGFVs is also not added to the official balance sheet, which in turn has allowed governments to borrow far beyond the permitted debt limits. This is what has been dubbed ‘hidden debt’ by the central government and has become a thorn in the side of the government and a crucial issue to be resolved.

Crisis in China’s property market

Concerns around the sustainability of China’s property sector have been circulating for many years. In 2016, the government first used the phrase “houses are for living in, not speculation”, in criticism of the rise in housing presales and purchases for investment.

In this section, we discuss how a government policy aimed at curbing lending and reducing debt in the property sector led to the fall of Evergrande, one of China’s largest property developers, and the cascading effect this has had upon the rest of the industry.

The three red lines policy

Recognizing the risk that the property sector’s debt posed to the economy, in August 2020, the PBOC and the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development held a meeting with other government departments to discuss mechanisms to curb borrowing and reduce debt in the property sector. In attendance in the meeting were 12 of China’s largest property developers – and were asked to take action to reduce debt.

The outcome of the meeting was a policy known as the “three red lines”. This policy (which has not been made public) requires that property developers must meet certain criteria before they can apply for refinancing.

The three red lines for real estate companies are:

- An asset-liability ratio (after excluding advance receipts) of no greater than 70 percent

- A net debt ratio of no more than 100 percent

- A cash to short-term debt ratio of one or below

At the time of the meeting, all the developers present at the meeting crossed at least one of the red lines. A year later, however, most were able to remain within the lines to apply for more loans, apart from two, one of which was Evergrande.

The Evergrande crisis

The three red lines policy has had a devastating impact on Evergrande, which, at the time the crisis began to unfold, was China’s second-largest property developer.

Evergrande had accumulated over US$300 billion in liabilities, which include US$19 billion in overseas bonds.

This meant that Evergrande still crossed all three of the red lines one year after the meeting and was no longer able to pay off or refinance its loans.

In December 2021, Evergrande defaulted on US$1.2 billion of its overseas bonds. Although this did not necessarily mean imminent collapse for the company, it heightened concerns over the company’s ability to repay the rest of its liabilities. In addition to institutional investors, it is possible the company would be unable to fulfil its obligations for the advance presales of unbuilt homes or be unable to repay the home buyers if the homes are never built.

Evergrande is also not the only property developer that has faced debt issues in the wake of the tightened policies. At around the same time as Evergrande’s default, the property developer Kaisa missed a US$400 million bond payment. In January of 2022, Shimao Group defaulted on a US$101m project loan, and most recently, Yuzhou Group requested a deferral for repayment of offshore bonds worth US$582 million.

Falling house prices

One of the consequences of the property market crisis is a fall in home prices. The inability for major property developers to repay their sky-high liabilities has shaken confidence in the sector and led to falling house prices, sales, and construction, all of which will have a knock-on effect on the economy as a whole.

Already indebted property developers have struggled to raise funds through sales, and in some cases have even gone as far as cutting prices in an attempt to lure homebuyers. This in turn has further undermined the valuation of their property, and, in some cases, led to protests by homeowners and intervention from the government.

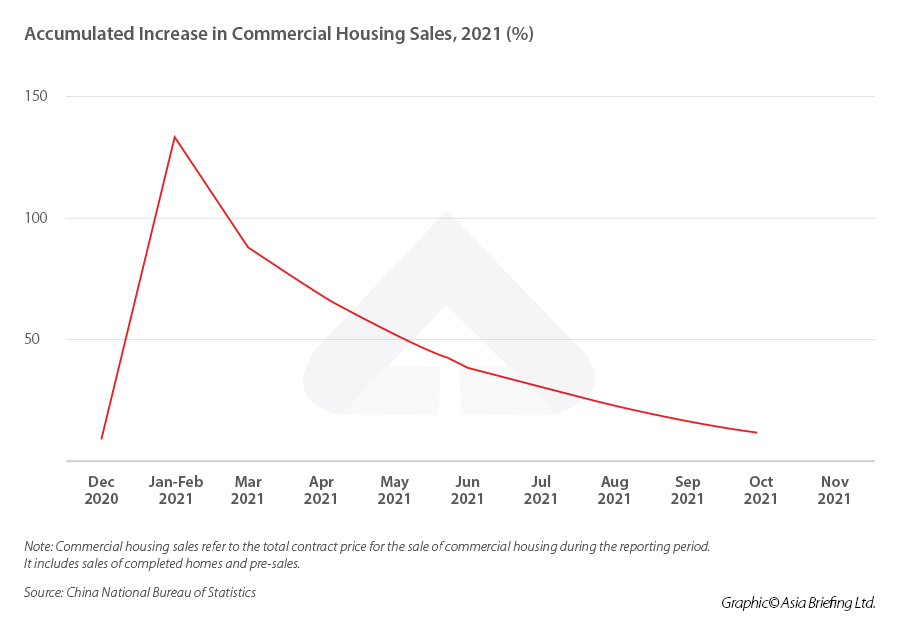

Although growth in house sales initially exploded at the beginning of 2021, the numbers quickly began to taper and turned negative during the second half of the year. According to data from CRIC, a provider of real estate information, sales among China’s top 100 real estate developers dropped by an average of 3.5 percent in 2021 from the previous year, with over 80 percent not reaching their annual sales targets by the end of the year.

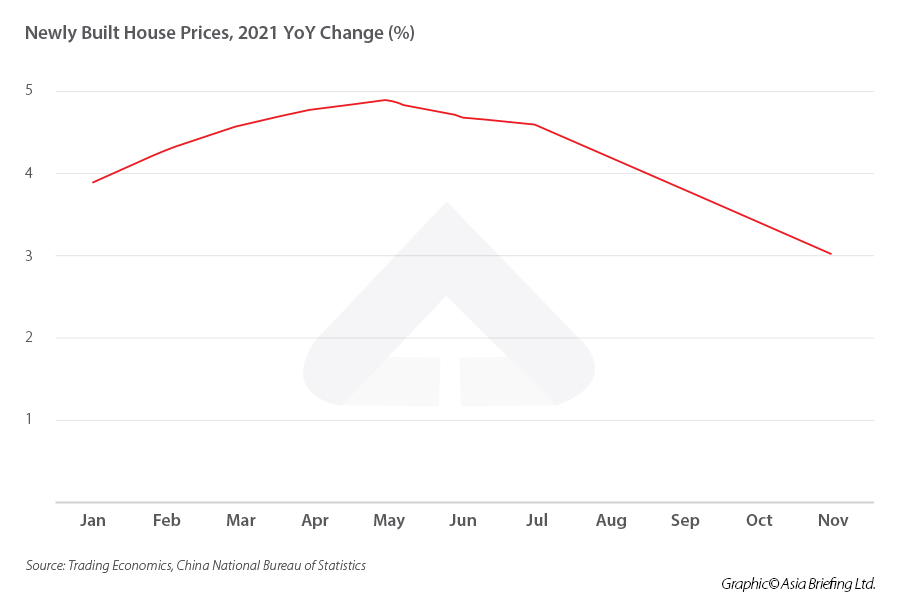

Meanwhile, the growth rate of prices of newly built houses continued to accelerate at the beginning of 2021 but then slowed in the latter half of the year, with the price of new homes in China’s largest 100 cities growing just 2.4 percent from the previous year, according to data from China Index Academy, a property research organization. That is the lowest growth rate recorded in the last seven years.

Much of the price drop was due to a contraction at the end of the year. However, data from December indicates that the trend may be reversing. In December 2021, the average price of new homes decreased by 0.02 percent from the previous month, but the decrease had slowed slightly from the 0.04 percent month-on-month drop in November.

Local government debt

The crisis in the property sector hasn’t just negatively impacted homeowners and property developers. As discussed above, local governments gain a significant portion of their budget from the sale of land-use rights, of which property developers are the biggest buyer.

Now the liquidity crunch in the property sector is being felt by local governments, who are already facing a mounting debt crisis of their own.

Data from the NBS shows that the area of real estate land acquisition decreased by 11.2 percent in November 2021 (latest available data). A research report from Tianfeng Securities, a securities consulting firm, also shows that most provincial governments experienced an overall drop in land transfers from the previous year. According to the report, 13 provinces and autonomous regions saw a fall in transfer fees of more than 20 percent year-on-year in 2021. Among them, seven provinces achieved less than 60 percent of their annual land transfer target, with Yunnan province experiencing the lowest rate at just 19 percent.

This has put even more pressure on local governments, who are also being asked to increase spending to stimulate the slowing economy and fuel recovery. Fewer funds coming from land sales may mean that governments will rely more heavily on LGFVs, which could further exacerbate the hidden debt issue that Beijing is keen to eliminate.

How is China tackling the property market crisis?

Easing criteria for debt refinancing

Although the central government appears to have been reluctant to directly bail out Evergrande and other indebted property developers, it is taking measures to ease the pressure on the industry, as well as local governments and other stakeholders.

One method has been to relax the three red lines policy to give developers more leeway to refinance their loans. Chinese media outlet Calianshe reported on January 6, 2022, that several large property developers had received notice from the government that it plans to exclude merger and acquisitions loans from the calculation of property developers’ debt and allow them to increase their debt level by five percent. This will make it significantly easier for companies with better liquidity to buy assets from indebted developers and help ease the pressure.

Although this may help to inject some liquidity into the sector, it is likely not enough to completely reverse the course for the sector as a whole. In general, it appears that the central government will not budge from its bottom line and is determined to get the market to address debt, which will mean continued pressure on property companies.

Increasing liquidity for local governments

In the face of plummeting land sales, one way in which the government has stepped in to ease the burden on local governments is by increasing the cap on the number of special purpose bonds (SPBs) that local governments can issue.

As discussed above, local governments were historically prohibited from direct borrowing (such as by participating in the bond market), leading to the rise of LGFVs. However, in 2015, recognizing local governments’ need for another cash stream and in an effort to wean them off of LGFVs, the central government began allowing local governments to issue SPBs. Through this scheme, local governments were also able to transfer some of their debt from the LGFVs to SPBs.

In late 2021, the Ministry of Finance (MOF) released RMB 1.46 trillion (US$230 billion) of the 2022 quota for SPBs in order to inject more liquidity and stimulate infrastructure spending. The funds raised are meant to be spent in the first quarter of 2022 to boost the slowing economy.

However, SPBs may not be a quick fix for liquidity issues. The government still strictly controls the types of projects they can fund (projects must be commercially viable and be able to repay the bonds that funded them). Facing a shortage of commercially viable projects to fund, local governments were slow to issue SPBs in 2021 and had to be urged to speed up the issuance of surplus bonds before the year was out.

In addition, funds raised from SPBs have at times been misappropriated and spent on projects outside the permitted scope. Further easing of the criteria for projects or offering more guidance on the proper allocation of funds would help local governments to spend more on infrastructure, stimulate the economy, and inject liquidity into the property sector.

Imposing a new property tax

A potential solution to the ‘speculative’ spending on homes is the introduction of a property tax, expanding it to cover tax on real estate for residential use.

In August 2021, President Xi Jinping took the most decisive step towards making it a reality, announcing a new pilot program to be rolled out in several cities across China. This decision feeds into the ‘common prosperity’ drive, as homeownership – in particular investment-driven purchases of second and third homes – is widely considered a source of wealth inequality in China.

The property tax, in theory, would provide another stream of income to local governments, diversifying away from a reliance on land sales and LGFVs. However, questions remain as to whether a property tax would be able to effectively replace the funds raised from land sales, which still far outstrip funds collected from property taxes in areas where such taxes are already levied.

In addition, a nationwide property tax would increase the tax burden on homeowners, which could, in turn, impact the real estate sector as property becomes a less lucrative investment option, which could then further impact land sales. Currently, however, the property tax has been levied mainly for commercial purposes, and excluded residential properties, therefore it is unclear how much local governments would be able to raise through universal residential property taxes.

2022 and beyond – what next for China’s property market?

The outlook of China’s property market in 2022 will depend largely on the kinds of policies the government chooses to implement. In a report released in December 2021, the PBOC forecast that investment in the property sector would grow between 2.5 and 5.5 percent in 2022 (link in Chinese). However, even the more optimistic end of the spectrum is still far below the seven percent year-over-year growth in investment seen in 2020.

Another report by UBS offers the following possible policies that could be implemented: further loosening restrictions on housing and development loans, relaxing capital market financing restrictions for developers, adjusting land transfer policies, and accelerating the construction of public rental housing.

The central government could also ease fiscal and monetary policies for local governments to promote infrastructure spending – although it is not certain it will do this, as it has consistently repeated the need for a “proactive fiscal policy and a prudent monetary policy”. Banks may also be encouraged to continue easing requirements for mortgages, which could help boost sales.

It is important to note that the policies that led to liquidity crunch in the property market were not implemented arbitrarily. It is evident that the government sees runaway debt as an existential risk to the economy and appears to be willing to sacrifice profits for some of the biggest property developers in order to rid the sector of the worst of its liabilities. It is also clear that the government wants to reduce its reliance on the property market for economic growth, and therefore may have a higher pain threshold in terms of the damage that can happen to the real estate sector.

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

Dezan Shira & Associates has offices in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, United States, Germany, Italy, India, and Russia, in addition to our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative. We also have partner firms assisting foreign investors in The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh.

- Previous Article What is ESG Reporting and Why is it Gaining Traction in China?

- Next Article Belt and Road Weekly Investor Intelligence #64