Leading Trends in China’s Services Sector After COVID Disruption

China’s services sector is the main driver of the country’s economic growth and the basis for the next stage in its development. Like other areas of China’s economy, however, it was disrupted by the COVID-19 outbreak – with potentially long-ranging consequences for its future trajectory.

From late January to mid-April, much of China’s economy was shut down amid lockdown measures to combat the coronavirus. Services providers – whether lawyers, educators, or programmers – had to pivot to remote work arrangements, while consumption patterns of services themselves also witnessed sudden shifts.

Since then China’s economy has stabilized, and many services industries have had to respond to now-permanent disruptions given the ongoing pandemic. As consumption habits change – the push towards greater digitalization accelerates. In this article, we examine China’s services sector and some of the disruptions and opportunities COVID-19 introduced in key subsectors.

China’s services sector at a glance

China’s unprecedented economic growth miracle over the past four decades was primarily driven by the manufacturing sector, which benefited from an enormous low-cost labor pool as the country opened to export markets. Now, as labor and land costs are growing and its workforce is increasingly well-educated, China is transitioning to a more sustainable post-industrial services and consumption-driven economy.

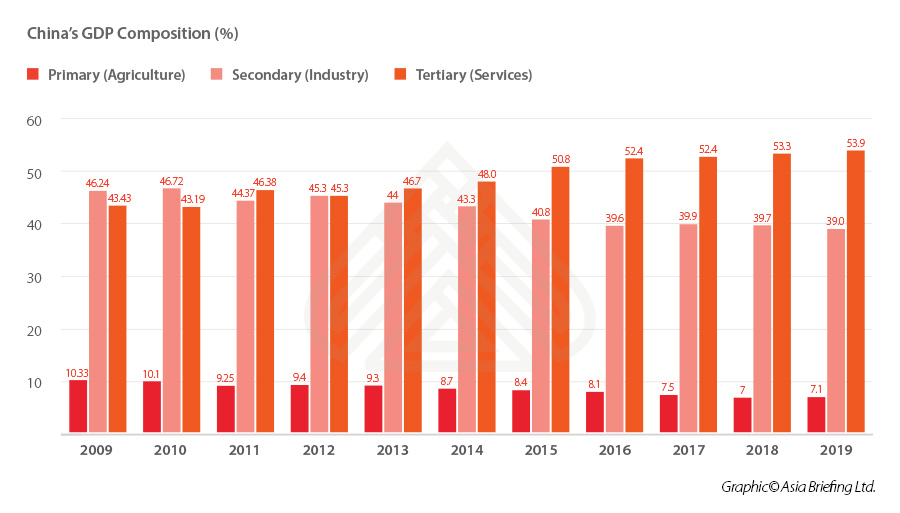

While growth in China’s manufacturing sector slowed over the past decade, the services sector grew at a faster pace. In 2009, the services sector represented 43.4 percent of China’s GDP, while in 2019 it was worth 53.9 percent of the GDP. Accordingly, the services sector is an outsized contributor to China’s growth – in 2019, it was responsible for 59.4 percent of total growth.

Nevertheless, while China’s services sector steadily grows with each passing year, it continues to lag behind fully developed economies. In the US, for example, the services sector represented over 77 percent of GDP in 2019, while in Japan it accounted for 69 percent.

Domestically, there is wide variation on the size of the services sector, based primarily on a given region’s level of development. For example, in Beijing and Shanghai – two of China’s most developed cities – the services sector was worth 83.1 percent and 72.7 percent of GDP, respectively, in 2019. In Wuhan and Qingdao – major but less developed cities – the tertiary sector was worth 53.3 percent and 55.4 percent of GDP, respectively, the same year.

In some smaller cities reliant on industry, the share of the services sector is even smaller. In Foshan – a mid-sized city in Guangdong, China’s manufacturing heartland – the services sector represented just 42.4 percent of GDP in 2019.

Put simply, wealthier regions tend to have stronger services sectors because these industries provide more value-added production than manufacturing and resource extraction. Services industries also need highly educated and specialized workers – like lawyers, accountants, doctors, and researchers – who command higher wages than most laborers. Moreover, households with more disposable income have greater capacity to consume services locally, compared to manufacturers that are often reliant on overseas export markets. Thus, it is no surprise that services industries like finance, professional services, information technology, healthcare, and education are the most advanced in China’s wealthiest cities.

Yet, while the services sector is strongest in first- and second-tier cities, lower tier ones offer the biggest growth potential. Economic planners hope that, as lower tier cities gradually lose their manufacturing advantages to low-cost alternatives like Vietnam and India, they too will develop services-driven economies staffed by China’s well-educated younger generations.

Opportunities after COVID-19

The COVID-19 outbreak dealt a significant blow to China’s services sector amid the country’s lockdown. With substantial parts of the economy shut down and hundreds of millions of people stuck at home while China curbed the spread of the virus, the services sector experienced a temporary but significant downturn. In February – at the height of the lockdown in China – the business survey by Caixin/Markit (that focuses on sentiment within smaller, private firms) showed that the services purchasing managers’ index (PMI) had fallen to an all-time low of 26.5, where any figure below 50 represents a contraction.

Since then, China’s economy has largely returned to normalcy. The Caixin/Markit services PMI rose to 54.8 in September, recording among the fastest rates of expansion over the past decade.

However, the outbreak and its lingering effects seem to have majorly disrupted some industries while changing the trajectory of others. In this section, we look at how the services sector has responded to market shifts and changes in consumer behavior.

Retail and e-commerce

COVID-19 has impacted both what consumers purchase and how and e-commerce platforms distribute goods. Chinese consumers spent less during the lockdown, as they were confined to their homes and faced economic uncertainty. In January and February, for example, retail sales fell by 20.5 percent year-on-year. Despite this collapse, however, online sales of physical goods still managed to increase by three percent during the same period, as consumers overwhelmingly flocked to e-commerce platforms.

The lockdown led to a huge increase in online grocery purchases, with sales of food products increasing 26.4 percent year-on-year in January and February. Partly as a result of COVID-19, the market research firm iiMedia Research has projected that China’s online grocery market will increase by 62.9 percent in 2020 to reach RMB 264 billion (US$37 billion) in revenue. Alibaba’s Hema platform, JD.com’s 7Fresh, and Pinduoduo currently dominate the online grocery market.

In contrast, while groceries and other stay-at-home products like workout equipment soared, sales of discretionary products like apparel and makeup sharply declined – to say nothing of big-ticket items like automobiles. While lockdown measures have now mostly ended, these trends may continue going forward, as Chinese consumers navigate an economic downturn and change their consumption habits accordingly.

To minimize spread of the virus, many apartment complexes now administer their own drop-off points for deliveries instead of having couriers deliver straight to the customer’s apartment door. In some cases, local communities are banding together to place bulk orders for groceries.

The surge in online groceries has put a strain on cold chain supply management, as operators struggle to handle supplies and distribution of fresh and perishable products. In light of this challenge, e-commerce operators are turning to artificial intelligence (AI) to establish efficient distribution strategies as well as collaborating with local brick-and-mortar grocery stores to ensure that products are fresh and quickly deliverable.

In a bid to spur consumption, in April this year, the Chinese government announced plans to establish 46 new cross-border e-commerce pilot zones – almost doubling the country’s total from 59 pilot zones. Examples of the new CBEC zones are Xiong’an New Area, Hebei province; Jiangmen, Guangdong province; Datong, Shanxi province; Jilin city, Jilin province; and Chongzuo, Guangxi province, among others. Examples of the established CBEC zones are Hangzhou, Zhejiang province; Guangzhou and Shenzhen, Guangdong province; Zhengzhou, Henan province; Chengdu, Sichuan province; and Xiamen, Fujian province, among others.

Cross-border e-commerce pilot zones are special jurisdictions designed to encourage foreign trade via e-commerce platforms and offer preferential policies like exemptions on VAT and excise taxes as well as reduced corporate income tax rates. With over 100 of these zones in place, foreign businesses selling via cross-border e-commerce platforms will be better placed to fulfil timely deliveries on orders across the country, making their products more competitive vis-à-vis those offered on traditional e-commerce platforms.

Live streaming

Unable to go to malls and other physical stores to test products during lockdown, Chinese consumers turned to live streaming platforms for information on products to purchase. The trend towards live stream sales was already strong before the outbreak – particularly in industries like fashion and makeup – but accelerated during lockdown, as viewers watched live streamers discuss their lives and exhibit products, often for hours at a time.

According to China’s Commerce Ministry, there were over four million e-commerce live streaming sessions in the first quarter of the year, many of which were held on platforms like Taobao, Kuaishou, and Pinduoduo. Taobao reported that the number of new merchants using the platform’s livestreaming feature increased by over eight times from January to February.

Most influential e-commerce live streams are hosted by internet influencers known as key opinion leaders (KOLs) or by celebrities paid by a company to showcase their products. During the COVID-19 outbreak, government officials from provinces like Hubei and Shandong even joined live streaming sessions in an attempt to promote local products from their regions. Foreign businesses also got in on the act, such as the luxury company Louis Vuitton, which hosted its first live streaming event in March.

In addition to showcasing and selling products, live streams became a popular way for users stuck at home during lockdown to stay active and social. Live streamers held activities as diverse as virtual workouts, musical performances, videogame tournaments, and karaoke events, often incorporating social aspects to allow the audience to participate.

Industry analysts estimate that live stream-driven sales account for between two and 10 percent of total e-commerce sales. This is a large enough figure that businesses need to incorporate live streams into their broader e-commerce strategies, particularly as consumers increasingly flock towards creator-driven platforms instead of traditional mediums.

Beyond direct sales, however, live streams are becoming influential platforms for determining how consumers view a given product more broadly, as views popularized through live streams diffuse into the wider consumer base. This means that live streams should not be seen only for converting direct sales, but also for building brand image. Foreign businesses opting the live streaming strategy of marketing should establish partnerships with KOLs who are followed by the business’ target demographics and represent the brand’s values and lifestyle.

Online education

Online education in China has been booming in the last five years. In fact, prior to the outbreak, market researchers projected China’s online education and educational technology market would grow by 12.3 percent to reach RMB 435.8 billion (US$61.5 billion) in 2020. Much of this market consisted of supplementary education, such as exam preparation, tutoring, and foreign language instruction.

The forced closure of schools and universities due to COVID-19, however, led to rapid growth in the online education market and put renewed emphasis on educational technology designed for institutional use. Schools and universities were forced to move online and use educational software to deliver lectures, manage class participation, and conduct online testing, among other functions.

With both educators and students growing familiar with online education during the pandemic, the use of educational technology (EduTech) will likely become more widespread going forward. Increasingly, EduTech will not just be used for distance learning and emergencies, but will get integrated alongside traditional offline classrooms.

Even for institutions that are not integrating EduTech with offline learning, however, the outbreak necessitated them to update their online education capabilities. Faced with the threat of another wave of the outbreak, educational institutions at all levels must now stay nimble and be prepared to pivot to online classes with little to no notice.

The market for online education in China is lucrative and rapidly growing but presents a complicated regulatory framework for foreign investors to navigate. Both education and online servicess are sensitive areas for the Chinese government, meaning its regulations for online education are particularly strict.

Among the regulations governing the industry are the Opinions on the Orderly and Healthy Development of Educational Mobile Internet Applications, which nine ministries jointly released in 2019. Further, amid the COVID-19 outbreak, in February 2020 authorities released the Opinions on Deepening Reform of Educational Supervision and Guidance System and Mechanism in the New Era.

These various regulations establish a legal framework for online education in China, which is still a relatively nascent industry. Together, the regulations impose supervision of online education products, such as through the creation of a national database, as well as oversight to promote a minimum quality of education. Foreign investors entering China’s online education market therefore must take measured steps to comply with the industry’s complex regulations.

Film industry

China recorded over US$9 billion in box office revenue in 2019, making it the world’s second largest film market after the US, which made over US$11 billion at the box office that year. This year, China was poised to continue its trajectory towards eventually surpassing the US to become the world’s largest film market. The market research firm Globe Newswire projects China’s film market to over double in size by 2025, reaching US$22 billion in revenue.

However, as movie theaters shut down due to COVID-19 linked control measures, distributors suspended the release of both domestic and foreign blockbusters alike. Further, film and TV production came to a halt.

Despite this situation, hundreds of millions of people stuck in their homes during lockdown – often with little to do – resulted in higher than ever demand for entertainment products. Upstart streaming platforms capitalized on this situation to release cancelled blockbusters directly to on-demand access, bypassing the industry’s traditional period of cinematic release exclusivity.

For example, the Chinese internet company Bytedance, which owns several streaming platforms including Xigua Video and Douyin, purchased rights to distribute the film Lost in Russia after it was dropped from cinemas due to the pandemic. The movie proved to be a success, garnering views from over 180 million users in the first three days it was made available. Following the success of Lost in Russia, the video streaming platform iQiyi followed suit, purchasing the rights to premiere the movie Enter the Fat Dragon.

These tactics may alter the way in which films are produced and distributed going forward. It may not be sustainable for streaming platforms to continue to purchase the rights to expensive blockbusters – Bytedance paid RMB 630 million (US$88.1 million) for the rights to Lost in Russia – but the company made an opportunistic move to attract new users by providing a product to a captive market.

While the shift to online will take time, the COVID-19 experience may push the industry towards more mid-budget films being produced and distributed directly by Chinese streaming platforms, as similar companies like Netflix and Amazon Prime have done overseas. This will not only upend how audiences watch movies, but also the ways in which movies are financed and produced.

In response to COVID-19’s disruption of China’s film industry, the government released preferential policies to offer relief to the industry and help its return to production. According to the Announcement about Supportive Tax and Fee Policies for the Movie Industry, released by the Ministry of Finance and the State Administration of Taxation in May, film companies can carry over losses incurred in 2020 for up to eight years. Further, the government is waiving cultural construction fees for film companies, starting retroactively from January 1, 2020 until December 31, 2020.

The supportive policies offered by the government will not only assist film companies already operating in China that were impacted by COVID-19, but also new entrants that begin operations before the end of the year. With film and TV companies having their productions disrupted due to the outbreak – and the resumption of US-based productions facing an even longer disruption – demand for fresh content produced in China will be high.

Accelerating digitalization

In some cases, the COVID-19 outbreak introduced impactful but likely temporary shocks to the services sector, such as in the case of declining cosmetic sales. In other areas, the virus is necessitating changes that are arguably contingent on the continued presence of the virus and the risk of new outbreaks, like the continued use of contactless delivery systems for e-commerce.

In certain industries, however, the coronavirus may have introduced lasting change. It may have, for example, permanently changed how people buy their groceries and how universities deliver education. Overall, the coronavirus has simply accelerated the digitalization of the services industry. As China navigates its transition from manufacturing to services and consumption, foreign investors that are agile and can adapt to satisfy shifting trends will be best placed to capitalize on the country’s new economic landscape.

This article has been adapted from the China Briefing magazine, “Opportunities for Foreign Investors in China’s Service Industries After COVID-19, which is available as a free download from the Asia Briefing Publication Store.

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

We also maintain offices assisting foreign investors in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, United States, and Italy, in addition to our practices in India and Russia and our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative.

- Previous Article Taking Advantage of China’s New Normal

- Next Article China’s New Mechanism to Handle Complaints by Foreign-Invested Entities