What is BEPS 2.0? OECD’s Two-Pillar Plan and Possible Impact on Multinational Enterprises

We explain what is BEPS 2.0, its framework for fairer distribution of global taxing rights, especially with respect to large multinational enterprises, and China’s exposure to these reforms on international taxation.

To address the base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) risks arising from the digitalization of the global economy, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) issued a statement on July 1, 2021, on reworking the framework for international tax reform.

Commonly referred to as BEPS 2.0, the new framework aims to ensure a fairer distribution of taxing rights is established with respect to the profits of large multinational enterprises (MNEs) and to set a global minimum tax rate.

As of July 9, 132 member jurisdictions out of 139 have agreed to the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS, including Mainland China and Hong Kong.

Such a broad consensus on the BEPS 2.0 framework marks a significant breakthrough in the OECD’s work over the years. The organization now seeks to finalize the technical details of the BEPS 2.0 package by October 2021 and implement the package in 2023.

The BEPS 2.0 represents the “first substantial renovation of the international tax rules in almost a century” and is expected to have far-reaching impact on many ‘tax-friendly’ countries and MNEs.

What is BEPS 2.0? Understanding the two-pillar plan

The BEPS 2.0 package consists of two parts, which is also called the two pillars:

- Pillar One is focused on profit allocation and nexus; and

- Pillar Two is focused on a global minimum tax.

Pillar One – profit allocation and nexus

Simply put, the aim of Pillar One is to make MNE groups pay taxes in the countries where they have users, even if they have no commercial presence there.

Initially, Pillar One was focused on taxing highly digitized businesses, which provide cross-border digital services. The scope was then broadened to include certain consumer-facing businesses.

Now it is targeting the largest and most profitable MNEs. According to the OECD’s statement, all MNE groups with global turnover above €20 billion and profitability above 10 percent (profit before tax) are targeted by Pillar One. (The threshold will be reduced to €10 billion after seven to eight years contingent on successful implementation. Extractive industries and regulated financial services are excluded from the Pillar One scope.)

The key elements of Pillar One can be grouped into two components: a new taxing right for market jurisdictions (where customers are based) over a share of residual profit calculated at an MNE group level (“Amount A”) and a fixed return for certain baseline routine marketing and distribution activities (“Amount B”).

The plan proposed that a certain portion (20 to 30 percent) of the residual profit (profit exceeding a 10-percent margin) of these MNEs should be taxed in the market jurisdictions.

It is estimated that Pillar One will impact 78 of the world’s 500 largest companies. Major international technology enterprises will account for around 45 percent – or US$39 billion – of the estimated total allocation of profits of US$87 billion (Amount A) that will be subject to scrutiny under Pillar One.

Before, EU countries struggled to reach consensus on unified digital tax rules, and over 20 countries around the world have either proposed, announced, or enacted their own digital service tax (DST) to tax overseas tech giants.

Thus, the OECD Statement confirms that Pillar One will replace the countries’ unilateral measures on implementing the DST. However, the Statement is silent on the timing for when the removal of all DSTs should occur.

Pillar Two – global minimum taxation

Pillar Two sets a global minimum tax rate (that is at least 15 percent) and targets large MNE groups with global turnover above €750 million.

Under Pillar Two, if the jurisdictional effective tax rate of an MNE group is below the global minimum tax rate, its parent or subsidiary companies will be required to pay top-up tax in the jurisdictions they’re located to meet the shortfall.

Pillar Two consists of a series of Global Anti-Base Erosion (GloBE) rules, including:

- Two domestic rules:

- An income inclusion rule (IIR), which would impose current taxation on the income of a foreign-controlled entity or foreign branch if that income was otherwise subject to an effective rate that is below a certain minimum rate; and

- An undertaxed payment rule (UTPR) which would either deny a deduction or impose a possible withholding tax on base eroding payments unless that payment is subject to tax at or above a specified minimum rate in the recipient’s jurisdiction.

- A treaty based rule, known as the subject to tax rule (STTR), which ensures that treaty benefits for certain related party payments (particularly interest and royalties) are granted only in circumstances where an item of income is subject to tax at a minimum rate in the recipient jurisdiction.

The Statement confirms that MNEs could see a global minimum tax at a rate of at least 15 percent (for the IIR and UTPR) as soon as 2023. It also specified that the minimum rate for the STTR will be between 7.5 percent and 9 percent.

The Statement suggests that Pillar Two should be brought into law in 2022, to be effective in 2023.

Possible impact of the global minimum taxes on countries and businesses

Although detailed implementation plans for the global minimum tax (as part of the BEPS 2.0 package) are not yet finalized, countries and multinationals are already weighing the possible impact.

The minimum tax rate may benefit most developing countries, which impose higher corporate income taxes, but it could blunt the appeal of some other countries, including tax havens. For example, Ireland in the EU is home to headquarters of several tech giants, including Facebook, Google, and Apple, and offers a corporate income tax rate of 12.5 percent. So far, the country has held out on signing the OECD proposal.

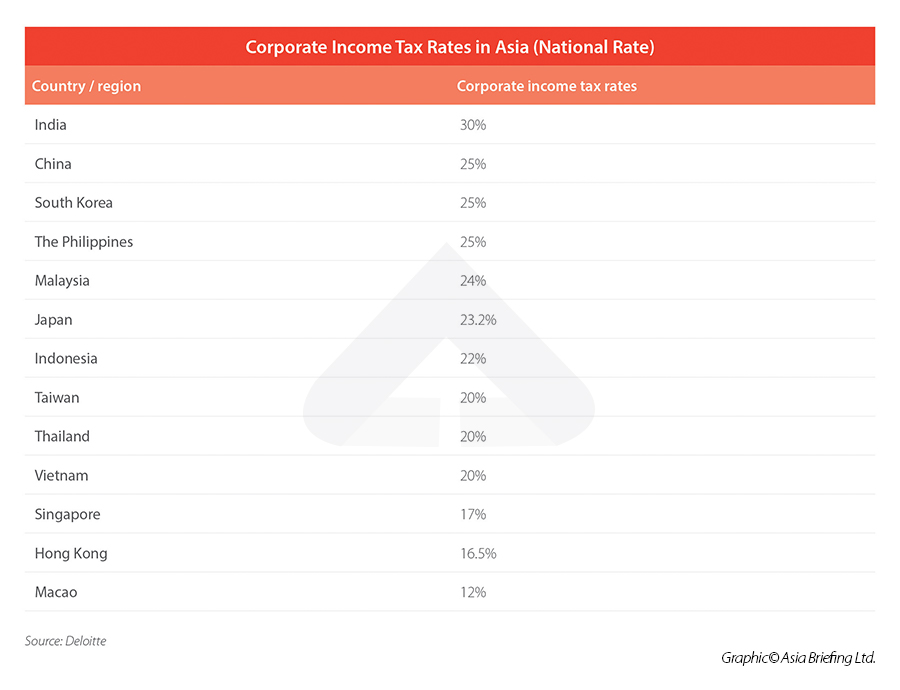

Among leading Asian economies, Singapore’s corporate tax is set at 17 percent, Hong Kong is 16.5 percent, and Macao is 12 percent – lower than most Asian economies. Taking in account various available tax incentives in these jurisdictions, the effective corporate tax rates in these regions can be even lower.

National level corporate tax rates in Asian countries

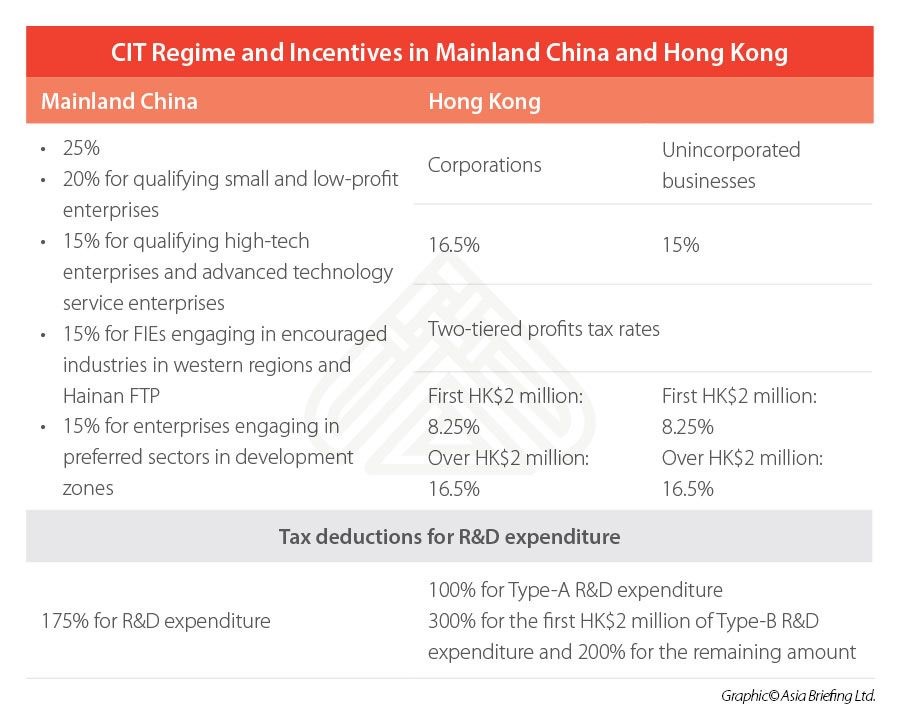

Tax rates in Mainland China and Hong Kong

What is China’s exposure to the new international tax rules being written under BEPS 2.0?

By comparison, China, with a national corporate income tax rate of 25 percent, is less exposed.

However, China does implement a wide range of tax incentives. For instance, some high-tech enterprises, enterprises engaged in encouraged industries in China’s western regions, as well as some enterprises registered in Hainan Free Trade Port may be able to enjoy an effective corporate income rate of lower than 15 percent.

Large MNEs from China need to measure the thresholds (their global turnover levels) at which the minimum tax rule is applied to assess whether they are within the scope.

Chinese technology titans, such as Alibaba and Tencent, which have divisions in the Cayman Islands, could also be hit by the two-pillar approach.

MNEs should carefully review the principal design elements agreed to in the OECD statement to determine how the proposals would impact their businesses and multijurisdictional tax liabilities, including whether any sector-specific exemptions in one region could result in tax shortfall in terms of global tax liabilities.

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com. Dezan Shira & Associates has offices in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, United States, Germany, Italy, India, and Russia, in addition to our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative. We also have partner firms assisting foreign investors in The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh.

- Previous Article Income Tax Subsidies for Overseas Talents in China’s Greater Bay Area: Application Process and Deadlines

- Next Article Investing in Zhongshan: Economic Data, Major Industries, and Incentives