Permanent Establishment Risks in China amid COVID-19: A Case Study

By Hannah Feng and Zoey Zhang

During the COVID-19 disruption period, governments of many countries have imposed measures like travel restrictions and quarantine requirements to contain the spread of the virus. As a result, many cross-border workers are stranded elsewhere, unable to physically perform their duties in their country of employment.

This has raised business concerns with regard to permanent establishment (PE) and tax residence risks. Will it trigger an entity’s PE status in a foreign jurisdiction? Will it subject the entity to tax filing requirements and tax obligations in that jurisdiction? Will it change the employee’s tax residence?

Here, based on a particular case study, Dezan Shira & Associates (DSA) provides a detailed analysis of the possible PE and tax residence risks in China in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Scenario

University A in the United States enrolled students from all over the world. When these international students were on campus in the US, the university employed them as research assistants and paid them through US bank accounts. However, due to COVID-19, many international students were banned from entering the US.

Among them, some Chinese students were stranded in China. University A is considering letting the Chinese students continue their research assistance work remotely and paying them through their US bank accounts. Another option is to have its wholly foreign-owned enterprise (WFOE) set up in China hire the Chinese students locally.

Key issues

University A prefers hiring the Chinese students directly as its own employees and paying them through US bank accounts compared to hiring them under its China WFOE. However, there are concerns about potential PE risks under the first option.

DSA study – PE risks in China amid COVID-19

OECD guidance

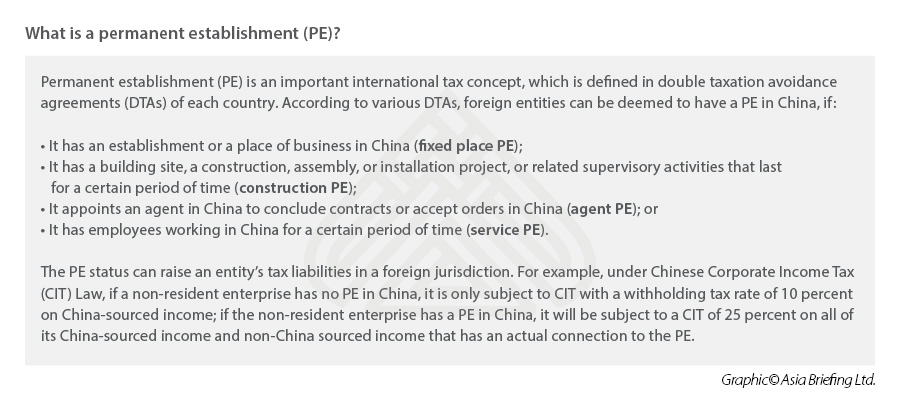

In general, China follows the rules of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) like the OECD Model Tax Convention, in defining PE. On April 3, 2020, the OECD published an analysis entitled “OECD Secretariat Analysis of Tax Treaties and the Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis” (OECD Analysis), providing guidance on cross-border tax issues arising from the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to it, “the exceptional and temporary change of the location where employees exercise their employment because of the COVID-19 crisis, such as working from home, should not create new PEs for the employer.” Most likely, University A’s situation would fall under “exceptional and temporary” and should not constitute a fixed place PE.

However, there is still a possibility that a service PE is constituted, where the OECD did not clarify how to assess a service PE during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, although the OECD rules are influential, they are not legally binding on authorities of various jurisdictions regarding PE assessment.

Explanation from China’s tax authority

Following the OECD, on August 14, 2020, China’s State Tax Administration (STA) released Q&As regarding PE and tax residence risks caused by the COVID-19. Similar to the OECD Analysis, the STA Q&As relaxed the assessment criteria for a fixed place PE, construction-site PE, and agent PE. For instance, it clarified that temporary home-based work during the epidemic prevention and control period, which is considered an “intermittent and occasional” activity, does not constitute a fixed place PE.

At this point, it is almost confirmed that University A would not be regarded as having a fixed place PE in China. However, the concern about service PE risks still has not been addressed.

We think that if Chinese authorities believe University A has a service PE in China, referring to the assessment criteria for fixed place PE, the service PE could have a chance to be deemed as “unintended” , thus to be exempt from PE tax liability. However, the enterprise will have to provide enough evidence to prove that the PE is “unintended” – the situation is out of the control of the employer.

US-China DTA

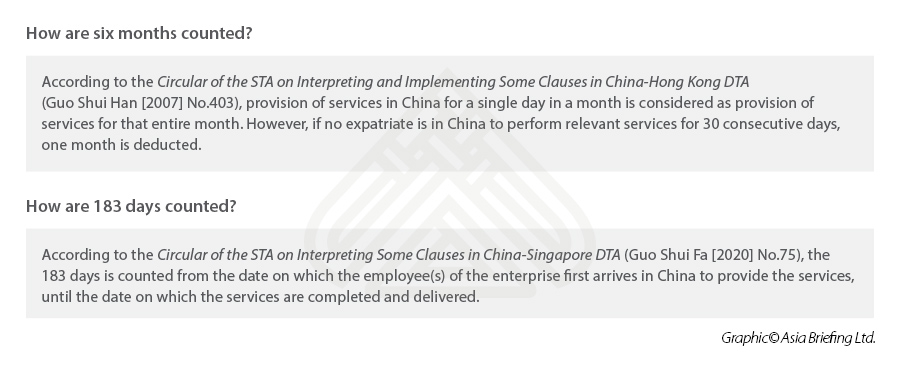

Regarding the service PE, the US-China DTA stipulates that PE includes “the furnishing of services…within the country for a period or periods aggregating more than six months within any twelve-month period.” This means that the US-China DTA would protect the university partially from triggering service PE status in China if the students’ presence in China is less than six months within any 12 consecutive months throughout the duration of the employment.

DSA study – six-month and 183-day rules

The US-China DTA follows the six-month rule, while most recent DTAs China signed are beginning to follow the 183-day rule. In any case, when assessing the service PE, the STA has clarified in the STA Announcement [2018] No.11 that the six-month rule (that is, “consecutively or cumulatively over six months within any 12 months”) in the service PE clause should be interpreted the same as and be implemented in accordance with the 183-day rule (that is, “consecutively or cumulatively over 183 days within any 12 months”).

Thus, when assessing the service PE of University A, we should follow the 183-day rule. This implies that all days with the Chinese students’ presence in China should be counted. Non-working days, such as weekends or holidays, would be counted as a day of presence, the same as actual working days.

In short, if the Chinese graduate students stay less than 183 days in 2020 in China, the tax risk exposure for University A can be mitigated under the US-China DTA. However, once it exceeds 183 days, then technically University A runs the risk of having a service PE in China.

Given the special pandemic situation, we think that if the students could finish out their research projects and stop working for University A within the next few months, the service PE risk of University A is likely to be low, even if the total days the students stay in China exceeds 183 days.

DSA study – connected projects

In general, the measure of the employee’s total days resided in China is based on two factors:

- The employment contract, based on which the assessment period of the PE can be traced back to the date of employment; and

- The number of days or months the employee stays in China from the start date of the employment contract.

To avoid higher service PE risks, there are a few points to be noted.

Firstly, PE can be assessed according to the master contract, thus the assessment period of the service PE in China could be measured from the start date of the master contract. This may increase the potential service PE risk. To mitigate the possible risk, the foreign entity is recommended to split the sub-contract from the master contract and re-sign the contract each year or for each project.

Secondly, when determining a PE, the relevant authorities are entitled to look into connected projects, that is, the projects which are sufficiently related to be added together. They may look for connectivity between projects to determine the project continuity, for instance, whether one project provides the foundation for another, or whether the projects are executed or supervised in the same way.

For this reason, in addition to splitting the contract, it is recommended that the foreign entity should re-outline the scope of work in each project.

In this case, DSA suggests that University A can re-sign the contract with the Chinese students each year and redraw the scope of research work of individual Chinese students, thus to limit University A’s potential tax liabilities in China. The contract should include a clause about the place of employment (making it clear that the work is not being conducted remotely from China or from another country) and a clause that the supervisor must monitor the number of days the students travel in China to “not exceed” six months during the duration of the contract. These clauses can be used to prove that the students’ remote work from China is “occasional” and is caused by the COVID-19 crisis.

DSA study – tax residence

Temporary change of duty station is usually unlikely to change an employee’s tax residency. In this case, Chinese students’ tax residency status will not be impacted by the special circumstances caused by the pandemic and travel restrictions.

Because the students are Chinese nationals, they will be considered tax residents of China. This means that the students as Chinese tax residents will be subject to individual income tax (IIT) on both their China-sourced income and worldwide income, no matter where they work or for whom they work. Therefore, even under normal circumstances when the Chinese students work in the US, they are liable for paying the Chinese IIT on their US-sourced income.

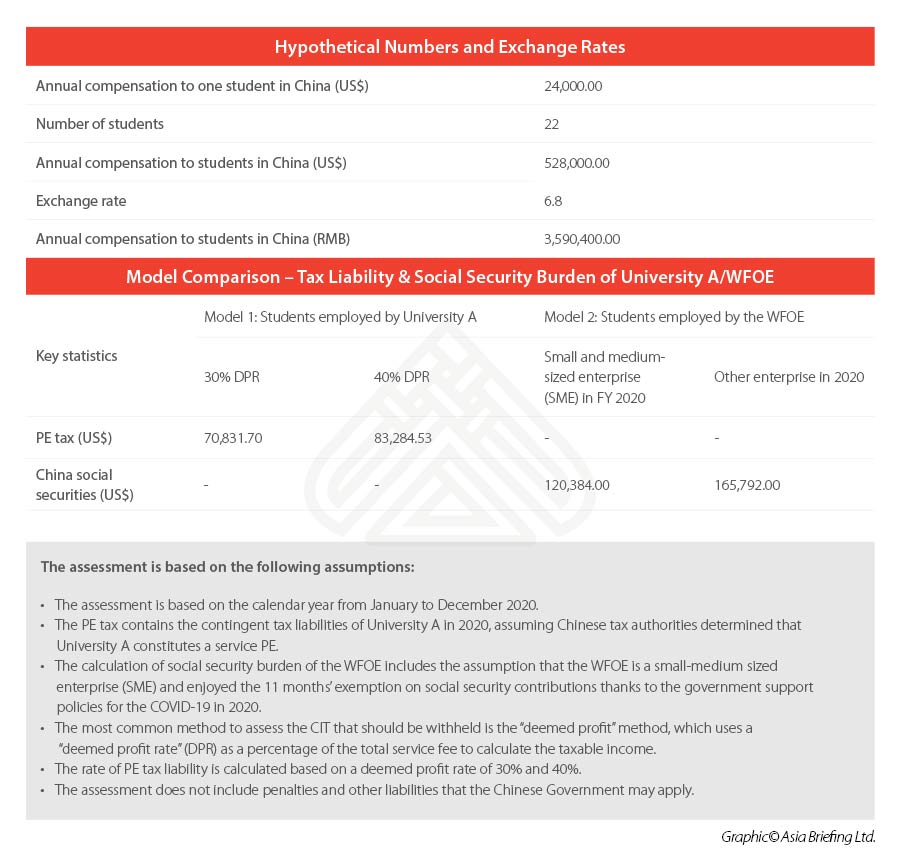

Analysis – comparing tax liability and social security burden of University A/Beijing WFOE

In the absence of a legal basis for identifying PE risks amid the COVID-19 pandemic, it is difficult to come up with a perfect solution for University A. However, between the two options – hiring the Chinese students directly under University A or hiring them locally under the Beijing WFOE, we calculated and compared the tax liability and social security burden under both options.

As the table shows above, if the Chinese students were hired directly by University A and University A paid annual compensation of US$528,000 to 22 Chinese students, the potential PE tax for University would range from US$70,832 to US$83,285 in 2020. If the Chinese students were hired by University A’s WFOE in China, the PE tax liability would be avoided, but the Chinese students and the WFOE will both be required to contribute to Chinese social security, which would range from US$120,384 to US$165,792. In practice, although the social security is usually paid by the WFOE, the WFOE can pass the social security burden to University A.

As the table shows above, if the Chinese students were hired directly by University A and University A paid annual compensation of US$528,000 to 22 Chinese students, the potential PE tax for University would range from US$70,832 to US$83,285 in 2020. If the Chinese students were hired by University A’s WFOE in China, the PE tax liability would be avoided, but the Chinese students and the WFOE will both be required to contribute to Chinese social security, which would range from US$120,384 to US$165,792. In practice, although the social security is usually paid by the WFOE, the WFOE can pass the social security burden to University A.

Summary

Change in the workplace caused by COVID-19 disruption may raise international tax issues, especially with regard to PE and tax residence risks. To address these concerns, the OECD and China STA issued commentaries in April and August. Both documents explain that if the change of the employee’s working location is caused by the COVID-19 and travel restriction measures imposed, it should not constitute a new fixed place PE in China, because the situation may fall under “exceptional and temporary” (in OECD Analysis) or considered an “intermittent and occasional” activity (in STA Q&As).

However, no official documents have yet clarified how to deal with service PE risks or how to determine the duration for a potential service PE. Thus, the potential tax liabilities of foreign companies and institutions with employees working remotely in China during the COVID-19 period are still unclear, and the Chinese government may still choose to impose taxes on foreign entities. What’s more, as bilateral relations between China and the US remain strained, we cannot fully predict the reaction by China for US foreign employers caught in these scenarios. If the employees will be staying in China for a long time (for instance, over six months), to completely avoid the potential PE risk, we would suggest that the foreign entity set up its own WFOE or have a professional employment organization (PEO) hire the employees.

For more information or advice on the potential tax liability status for companies without a presence in China and for assistance with individual short-term employees tax status in the country, you are welcome to email us at tax@dezshira.com.

About Us

China Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The practice assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Please contact the firm for assistance in China at china@dezshira.com.

We also maintain offices assisting foreign investors in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, United States, and Italy, in addition to our practices in India and Russia and our trade research facilities along the Belt & Road Initiative.

- Previous Article Exporting Meat Products to China During COVID-19: What You Need to Know

- Next Article Chinas Exportkontrollgesetz erklärt