So What’s the China Deal with India and Vietnam?

Op-Ed Commentary: Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Jan. 31 – As stories begin to break about concerns over the Chinese economy, and the slowdown that this would invariably bring, what are the potential impacts that resurgent Indian and Vietnam markets could instead bring to the table? Our firm, Dezan Shira & Associates, has been operational in each of these markets for some considerable time now. Next year, we will celebrate twenty years of legal and tax advisory services in China, from our ten offices there. In India, it will be five years and five offices, and in Vietnam, four with two offices . These are not small operations, either. In each country we operate in, we have applied for, and been granted, the requisite operational licenses, invested the required registered capital standards, and employ staff managed by a National Country Manager.

As far as I am aware, no other practice has either that specific reach or experience, although of course pretenders drop by and comment from time to time as these markets start to look more attractive. However, as we learned a long time ago, when it comes to professional services, there’s no substitute for having your own people on the ground, running a business, and dealing with clients as a direct result of possessing that first-hand knowledge. Sub-contracting work to local firms in such countries, as some practices do, is misrepresentative of the actual licensing required and is not enough to delve deeply into the real issues concerning on the ground work. The fact that so many do attempt to comment on these issues without actually having a presence there is therefore a matter of some wry amusement, at least to us. It means that there is a lot of nonsense spoken about markets by people whom neither have the financial commitment to providing said advice, nor regulatory expertise dealing with them.

It’s a matter I hope to address in this piece, especially as concerns about a potential China slowdown develop. It’s a scenario that is gaining increasing credibility, and something which we have highlighted through a variety of recent articles: “China Bears Gathering As Analysts Question Economy”, “China’s Dragon Playing With Fire” and “China’s Credit Bubble About To Burst” . All involve theories concerning a growing gap between Chinese incomes and the cost of living, struggles with inflation, and an apparent battle of wills between the Central Government and Chinese property speculators. If things do grind to a halt, growth in China will regress, and multinational corporations that have grown accustomed to putting ten percent growth or more on their shareholders balance sheets at the end of each year will be punished. India and Vietnam, not to mention the rest of Asia, seem to offer a potential way out of this. But what are the real deals that these countries offer when held up to China? Let’s examine each of these markets in brief:

India

For a long time, the issue with India has always been its infrastructure. Second, endemic corruption and third, bureaucracy. In fact, all of the problems associated with each of these exist. However the key to understanding India lies in the degree of the issue. In terms of infrastructure, it’s a no-brainer. India’s infrastructure needs, and is getting, a major overhaul. In terms of getting finance into the literally thousands of medium-big ticket projects that are going on, India’s Government is offering shares and financing in these projects to foreign investors. Often packaged under the term “Public-Private Partnerships”, these spell out how foreign investors can enter into these projects, obtain funding, and participate in the reconstruction of the country. We wrote about this extensively in this issue of India Briefing Magazine. In short, foreign investors involved in infrastructure development—engineers, contractors, architects, materials suppliers and so on—all need to get into the India market much as they did in China. The opportunity is now.

Concerning corruption, in India, it is endemic. However much of the impact on foreign businesses exists with the “baksheesh” request—a small “bribe” more often akin to giving a tip for processing a document. Typically running at just a few hundred rupees (a matter of cents), it is annoying, yet all pervasive. Concerning large-scale corruption, there is of course collusion between government officials and businesses—as occurs in all governments. Yet, India does maintain press freedom, and if caught, such protagonists can expect a literal trial by public fire. By contrast, the Communist Party sweeps much of what goes on in China under the rug. India’s bureaucracy is also not as bad as it’s painted—we know this first-hand as we run five offices assisting foreign investors in the country. Filings for the establishment of foreign invested offices, factories and so on are a daily occurrence for our firm. Just as one example, compared to China, it takes one step less in India to set up a representative office. The bureaucratic difficulties associated with doing business in India are over-hyped.

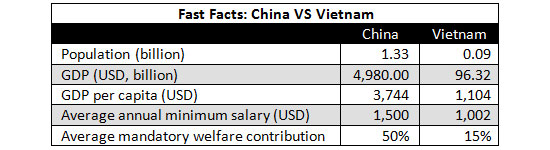

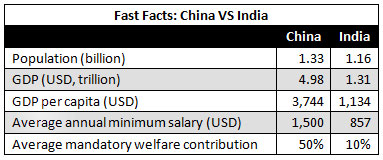

India also has a number of other things going for it. Its working population is young and accordingly much less expensive than China, and add-on expenses such as social welfare payments are at just 20 percent of China’s levels. India’s reforms are also gathering pace—a reduction in both corporate income tax and individual income tax is expected this year—which is a move that will reduce the levels of both from 45 percent down to 30 percent. That is about to make India highly competitive to China in terms of both labor costs and income tax.

Finally, there’s the matter of India’s own middle class. India has a huge middle class and a taste for foreign goods. India’s population is quickly catching up with China’s, and whereas China’s myth of a billion consumers has been around for centuries, India’s close match to this market size, coupled with an economy that is becoming more open rather than closed, means foreign businesses in India have not just an opportunity to conduct cheap manufacturing, but also sell to the local market. In this regard, as export manufacturing costs make China prohibitive, India is now one of the few countries where both cheap labor and a wealthy consumer class go hand in hand. Our China-India 2011 comparison , which includes labor costs, taxes and so on can be downloaded for free and provides much additional data concerning these perspectives.

Vietnam

Vietnam, meanwhile, is also booming, but for different reasons. Sharing a northern border with the far South-West of China, it offers both a refuge for previously South China-based factories having to cope with rapidly increasing labor costs, as last week’s article on Guangdong Province raising its minimum salary level twice in six months ably demonstrates. Wages in Vietnam run at a significant discount to China, as do the mandatory welfare payments, making the shifting of labor-intensive industries to the long east coast of Vietnam a more attractive economic proposition. This is in addition to access to a new developing market—that of the ASEAN bloc. Inter-ASEAN trade, now largely duty free, is worth some US$1.5 trillion, with a market of some 580 million people. As neither China nor India are members of ASEAN, moving operations to Vietnam, which is a member, gives a distinct advantage in avoiding duties. The ASEAN bloc consists of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam, and if combined as one nation, it would be the ninth largest in the world. Vietnam, with an improving export driven infrastructure, low wages, and access to the ASEAN free trade market, is quickly emerging as an attractive destination.

Like China, it too has been making use of Free Trade and Industrial Zones to assist with the facilitation of foreign investment into the country, a subject we again discussed in some detail in this issue of Vietnam Briefing Magazine . Vietnam still offers significant tax incentives to do so, something which China largely dropped from its investment agenda a few years back. We also wrote about the feasibility of relocating a factory from South China to Vietnam in this article “From China To Vietnam For Labor Intensive, Export Driven Manufacturing” a piece that compared costs and included the redundancy payments for laying off Chinese workers in the process. Vietnam, it is apparent, is a serious contender for picking up export processing business from China.

Emerging Asia also of course impacts the movement of investment opportunities in the region, especially as far as China is concerned. We have discussed these issues also in some length in our piece “China Near Top For Wage Overheads In Emerging Asia” , in addition to examining some of the other Asian emerging market issues in the articles “Cambodia, Laos & Vietnam – Indochina and China Today” and “ASEAN Summit Seeks Increased Regional Links.”

As China looks to experience a period of some decline in growth, both India and Vietnam offer solid opportunities for foreign investors to be able to make that up, as does the ASEAN trading bloc as a whole.

Other related information such as published articles, complimentary websites and magazines of use may be found as follows:

Asia Trade, Labor & Comparator 2011

Our detailed analysis of nineteen Asian countries, including China, India & Vietnam, their labor costs, mandatory welfare, demographics, and trade statistics

China-India 2001 Developments Trends & Demographics

China-India 2001 Developments Trends & Demographics

Complimentary Download

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the founding partner and principal of Dezan Shira & Associates, a foreign direct investment practice specializing in FDI investment laws, taxes and operations. The practice has been extant in Asia since 1992. Chris is the Vice Chairman of the UNDP Business Advisory Council for the region. The firm’s brochure may be downloaded here.

- Previous Article 2011 Shanghai Consumer Sentiment Report Available

- Next Article Top 10 Chinese Films for the Chinese New Year