China’s Infrastructure Dominance: Still a Step Ahead in Asian Manufacturing

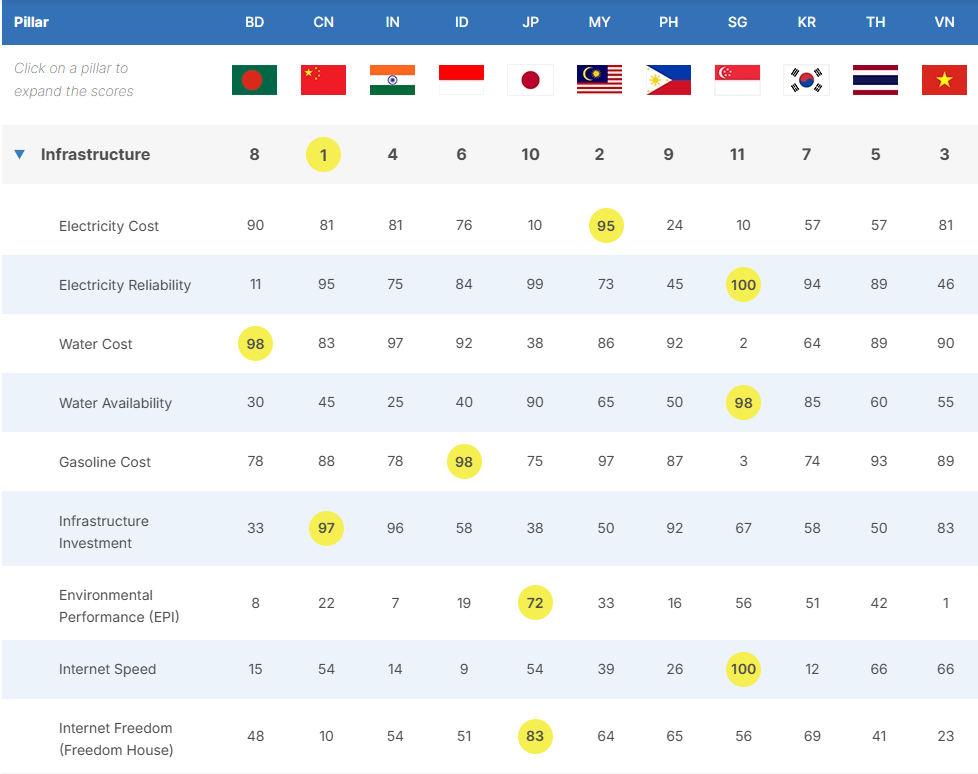

Infrastructure is a foundational input shaping manufacturing efficiency, scalability, and operational predictability. Beyond basic transport connectivity, infrastructure encompasses logistics networks, industrial platforms, energy and utilities systems, and digital connectivity, all of which directly affect production costs, supply chain coordination, and the ability of manufacturers to operate at scale. For this reason, infrastructure continues to feature as a core indicator in comparative assessments of manufacturing environments across Asia, including our Asian Manufacturing Index (AMI) 2026.

China’s manufacturing ecosystem has been underpinned by sustained infrastructure investment over multiple decades, resulting in dense transport networks, integrated industrial zones, large-scale energy capacity, and advanced digital infrastructure. As manufacturing activity gradually diversifies across Asia, questions have emerged regarding whether China’s infrastructure advantage remains material relative to emerging alternatives.

This article examines China’s infrastructure positioning in the context of Asian manufacturing competitiveness, focusing on transport and logistics networks, industrial ecosystems, energy and utilities infrastructure, and digital infrastructure.

Overview of China’s infrastructure development framework

China’s infrastructure development framework has evolved over the past two decades from a focus on large-scale physical connectivity to a more integrated model that combines transport, energy, industrial platforms, and digital systems.

In the early 2000s, infrastructure investment was largely oriented toward addressing basic deficits in transport, power supply, and logistics capacity. National expressways, railways, ports, and energy networks were expanded rapidly to support China’s emergence as a manufacturing and export hub. This phase was characterized by extensive capital deployment, strong central coordination, and an emphasis on scale, which significantly reduced physical bottlenecks and improved nationwide connectivity. Over time, this approach laid the groundwork for manufacturing concentration along key economic corridors and coastal regions, while also facilitating the gradual extension of infrastructure networks into inland and western provinces.

More recently, China’s infrastructure investment model has shifted toward greater integration and system efficiency. While traditional transport and energy projects remain important, infrastructure planning has increasingly been aligned with industrial policy objectives, technological upgrading, and supply chain resilience.

Central planning mechanisms, including successive five-year plans and sector-specific development strategies, continue to play a coordinating role in setting priorities, sequencing projects, and allocating long-term capital. At the same time, implementation has become more diversified, with a greater role for local governments, state-owned enterprises, and, in selected areas, private and market-based participation.

Within this framework, infrastructure development functions less as a standalone policy objective and more as a supporting platform for manufacturing ecosystems. Industrial parks, development zones, and logistics hubs are typically planned alongside transport links, utilities, and digital infrastructure, allowing production, distribution, and supporting services to co-locate.

Transport and logistics infrastructure: Coverage, density, and efficiency

Transport and logistics infrastructure has been a central pillar of China’s manufacturing development, underpinning the movement of inputs, intermediate goods, and finished products across an increasingly complex national production network. National and international assessments of logistics performance offer a structured view of this infrastructure. According to the most recent World Bank Logistics Performance Index (LPI), which benchmarks trade logistics across economies, China’s score for the quality of trade- and transport-related infrastructure was reported at around four on a five-point scale in 2022.

China’s expressway and freight rail networks have expanded substantially over the past two decades, creating dense transport corridors that link coastal manufacturing hubs with inland production centers and global export gateways. These networks have lowered transit times between production sites and ports, contributing to more reliable logistics operations for manufacturers. Beyond physical transport assets, China’s logistics ecosystem increasingly incorporates bonded zones, integrated transport hubs, and customs facilitation mechanisms that reduce administrative friction and enable closer coordination between production and distribution functions.

Port infrastructure constitutes a critical component of this framework. China is home to a significant share of the world’s busiest cargo terminals, including deep-water and container ports that handle large annual freight volumes. For example, major ports on the eastern seaboard handle hundreds of millions of tonnes of cargo annually, supporting both domestic supply chains and international trade flows. In addition to coastal port capacity, inland river ports (such as those along the Yangtze and other major waterways) serve as multimodal logistics hubs, linking waterway freight with rail and highway connections and facilitating efficient inland access to global shipping routes.

These transport and logistics capabilities align with broader connectivity initiatives that integrate land, sea, and regional transport corridors. Projects such as the New International Land-Sea Trade Corridor extend inland connectivity by linking central Chinese hubs with coastal ports and international markets, allowing manufacturers to diversify logistics pathways and strengthen resilience against disruptions.

At the same time, China’s transport and logistics advantages are not uniform across all regions. Disparities persist between more developed eastern coastal areas, where connectivity is highest, and interior or western regions, where infrastructure continues to catch up. Rising maintenance costs and congestion pressures in mature corridors have also become more prominent considerations for planners and operators.

Industrial parks and development zones as integrated production platforms

China’s industrial parks and development zones operate as integrated production platforms designed to concentrate manufacturing activity within environments that combine infrastructure provision, administrative coordination, and sectoral specialization. By the end of 2024, China had established 232 National Economic Development Zones, hosting a total of 60,000 foreign-invested companies.

These zones are structured to integrate utilities, transport access, and regulatory services within a defined geographic footprint. Power, water, wastewater treatment, and telecommunications infrastructure are typically planned alongside production facilities, while many zones provide bonded logistics areas, on-site customs clearance, and streamlined administrative services. This reduces coordination costs for manufacturers and facilitates closer alignment between production, logistics, and compliance functions. Supplier proximity is a further defining feature, with upstream and downstream firms often co-located within the same zone or adjacent industrial clusters.

In economic terms, development zones play a central role in China’s industrial ecosystem. Official government communications consistently highlight their importance in attracting foreign direct investment, supporting export-oriented manufacturing, and driving industrial upgrading. Although they occupy only a limited share of the national land area, these zones serve as concentrated hubs for high-value industrial activity. Over time, their sectoral focus has increasingly shifted toward advanced manufacturing segments such as electronics, automotive supply chains, new materials, and high-end equipment manufacturing.

Energy and utilities infrastructure: Capacity, reliability, and industrial support

Energy and utilities infrastructure continues to serve as a critical enabler of large-scale manufacturing activity in China. By the end of 2024, the country had added 373 million kilowatts of new renewable energy installed capacity during the year, marking a year-on-year increase of 23 percent. This brought China’s total cumulative renewable energy capacity to 1.889 billion kilowatts, supported by a nationwide power grid that links key industrial hubs across coastal, central, and western provinces.

Beyond aggregate capacity, grid reliability and regional balancing mechanisms play an important role in production continuity. China operates multiple synchronized regional power grids linked by ultra-high-voltage (UHV) transmission lines, enabling large-scale electricity transfers from energy-rich western regions to manufacturing-intensive eastern and coastal provinces. This interregional connectivity reduces exposure to localized supply disruptions and supports stable power availability for energy-intensive industries.

Renewable energy deployment has become increasingly integrated into this framework. By 2025, China accounted for more than 50 percent of global installed solar and wind capacity, alongside continued investment in grid-scale energy storage and smart grid technologies. Grid modernization efforts, including digital monitoring and automated dispatch systems, have improved load management and facilitated the integration of variable renewable sources, supporting advanced and sustainability-oriented manufacturing operations.

Digital Infrastructure and manufacturing digitalization

Digital infrastructure (encompassing next-generation networks, broadband connectivity, and data processing platforms) has become an intrinsic enabler of modern manufacturing systems. In China, national strategies such as Digital China and the expansion of new digital infrastructure have prioritised the deployment of broadband and 5G networks as foundational elements supporting economic transformation. By the end of 2025, China had activated more than 4.83 million 5G base stations, reflecting the extensive scale of its wireless network build-out. This coverage has facilitated integration of 5G applications across a wide range of economic sectors, including manufacturing, logistics, and industrial services.

Broadband connectivity in China has similarly expanded, with the total number of broadband access ports approaching 1.2 billion as of December 2024, highlighting the breadth of fixed-line and mobile internet infrastructure supporting digital adoption.

At the same time, the number of internet users in China surpassed 1.1 billion, indicating deep penetration of digital platforms and services into both consumer and business contexts. Collectively, these developments have underpinned conditions in which digital tools and data flows can be leveraged in production, supply chain management, and enterprise coordination.

In major manufacturing regions, digital infrastructure has increasingly supported automation, data-driven production management, and smart logistics systems. Industrial enterprises have adopted a range of digital technologies (from real-time sensor networks and predictive maintenance platforms to cloud-based analytics and AI-assisted quality control) that enable greater responsiveness to demand fluctuations and operational disruptions. Empirical research suggests that such digital infrastructure contributes directly to industrial development by enhancing information accessibility, lowering transaction costs, and fostering coordination across geographically dispersed production activities, while also interacting with transportation and market infrastructure in ways that mitigate uneven regional development.

The adoption of digital systems among large industrial enterprises is further supported by China’s broader institutional focus on data capacity and digital ecosystems. National planning frameworks to 2025 and beyond have emphasised the expansion of computing power infrastructure, data centers, and platform-level coordination mechanisms as integral components of a modern industrial system. This reflects an understanding that digital connectivity alone is insufficient: high-capacity data processing and integrated application environments are necessary to translate connectivity into productivity gains and innovation potential.

China v.s. other Asian countries digital infrastructure

Comparatively, digital infrastructure readiness across other Asian manufacturing economies varies widely. In Southeast Asia, investments in 5G vary by market, with the regional 5G infrastructure market valued at approximately US$1.07 billion in 2025 (a relatively nascent stage compared with China’s network scale) and projected to grow significantly over the coming decade.

Individual economies such as Singapore have achieved high early 5G population coverage and fostered private 5G testbeds that support industrial and urban applications, but comprehensive digital infrastructure ecosystems are still evolving across much of the region.

India’s telecom sector has similarly accelerated its 5G rollout, reaching around 85 percent population coverage by late 2025, reflecting substantial progress but also indicating a digital infrastructure build-out that remains behind China’s in absolute scale. Data center capacity in markets such as India is also expanding rapidly but remains under-penetrated relative to the size of digital demand, highlighting ongoing gaps in core processing infrastructure.

|

Comparative Digital Infrastructure Metrics: China vs Other Asian Economies (2025) |

|||

| Metric | China | India | Southeast Asia (Regional) |

| 5G Base Stations (2025) | ~4.83 million deployed nationwide, reflecting extensive network capacity and reach | ~518,854 5G base transceiver stations (BTS), according to data from the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) | Regional market valued at ~US$1.07 billion in 2025, with deployment varying by country (for instance, Singapore >95% population 5G coverage) |

| Broadband Subscribers | ~691 million to 697 million, with a net increase of over 20 million in 2025 | Reached the 1 billion mark in November 2025 | Not uniformly measured regionally; individual markets vary significantly in fixed broadband penetration (ICT development gaps persist) |

| Data Centre Market Share (APAC) | Holds 34% to 46% of the APAC region’s colocation investment share in 2024-2025 | India’s data center (DC) market is experiencing rapid expansion, with total capacity surpassing 1.5 GW by late 2025. | Local and global data centre investments increasing (Thailand ~US$ 2.7 billion initiatives), but still nascent relative to China; regional data centre infrastructure expanding |

| Cloud & Compute Infrastructure | Major cloud operators (Alibaba, Tencent Cloud) with wide CDN and regional presence | The Indian government is increasing cloud use with programs such as Digital India, IndiaAI, and the National E-Governance Plan. The country has a consolidtaing, but smaller overall, compute footprint compared to China; substantial investment boom underway | Regionally speaking, Southeast Asia’s cloud and computer infrastructure is experiencing a massive boom, projected to exceed US$50 billion in colocation market value by 2030 |

| Digital Inclusion & IPv6 Adoption | Significant IPv6 deployment underway with large shares of active IPv6 users reported | Rapid broadband and mobile growth, but IPv6 adoption and next-gen network standards vary by region (fewer centralized programmes reported) | Digital divide persists in rural areas and lower-income nations; infrastructure and affordability gaps remain |

Infrastructure and supply chain resilience

Infrastructure density and system redundancy have become increasingly relevant factors in supply chain continuity, particularly as manufacturers reassess exposure to external shocks. In China, the breadth of transport, logistics, and utilities infrastructure provides multiple layers of redundancy that can be activated when individual nodes or corridors are disrupted. Dense expressway and rail networks, combined with multiple major ports along the eastern seaboard and extensive inland waterway systems, allow logistics flows to be rerouted with relatively limited interruption.

This flexibility has practical implications for manufacturers. The ability to diversify port usage, shift cargo between transport modes, or adjust production geographically within the same national system reduces dependence on single routes or facilities. During recent stress events, including pandemic-related disruptions and localized weather or energy constraints, China’s infrastructure network enabled a faster normalization of industrial activity than in many peer economies, where logistics bottlenecks were more difficult to bypass.

At the same time, infrastructure resilience does not eliminate supply chain risk. Instead, it contributes to operational predictability by lowering the probability that disruptions will escalate into prolonged shutdowns. Infrastructure density allows manufacturers to absorb shocks through substitution and reconfiguration, rather than relying on just-in-time precision alone.

In this sense, China’s infrastructure supports continuity and the capacity for adjustment, rather than guaranteeing uninterrupted operations under all conditions.

Constraints, costs, and trade-offs

Despite its scale and maturity, China’s infrastructure model faces growing constraints, which include, among others:

- Maintenance costs for transport, energy, and utilities infrastructure have risen steadily, placing pressure on local government finances, particularly in regions with slower economic growth or high legacy debt. These fiscal pressures have prompted greater scrutiny of new infrastructure investment and increased emphasis on efficiency, consolidation, and asset optimization.

- Environmental compliance requirements also shape infrastructure use and expansion. Stricter emissions controls, energy efficiency standards, and sustainability targets affect both infrastructure operators and industrial users, influencing project approval timelines and operating costs. While grid modernization and renewable energy deployment have mitigated some pressures, manufacturers in energy-intensive sectors continue to face evolving regulatory and pricing dynamics.

- Regional imbalances remain another structural constraint. Infrastructure quality and access are strongest in coastal and core industrial regions, while parts of inland and western China continue to lag, despite ongoing investment. For manufacturers, these disparities translate into uneven operating conditions depending on location.

- These constraints interact with broader cost considerations, including labor costs, regulatory compliance, and geopolitical risk. As a result, infrastructure strength alone does not offset all competitive pressures, but instead forms one component of a more complex cost-benefit calculation.

Conclusion

China’s infrastructure represents a long-term, capital-intensive advantage that is difficult to replicate quickly. Decades of coordinated investment have produced dense transport networks, integrated industrial platforms, reliable energy systems, and advanced digital infrastructure that continue to support manufacturing scale, coordination, and adaptability.

At the same time, infrastructure alone does not determine manufacturing outcomes. Labor dynamics, regulatory conditions, market access, and geopolitical considerations all shape investment decisions. Infrastructure instead functions as a risk-shaping factor, influencing operating predictability, scalability, and adjustment capacity rather than guaranteeing competitiveness in isolation.

Looking ahead to 2026 and beyond, infrastructure realities suggest that China will remain a central manufacturing platform within Asia, even as diversification accelerates elsewhere. For manufacturers, the strategic question is increasingly not whether to move away from China entirely, but how to balance exposure across markets while continuing to leverage the structural advantages embedded in China’s infrastructure system.

About Us

China Briefing is one of five regional Asia Briefing publications. It is supported by Dezan Shira & Associates, a pan-Asia, multi-disciplinary professional services firm that assists foreign investors throughout Asia, including through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Haikou, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong in China. Dezan Shira & Associates also maintains offices or has alliance partners assisting foreign investors in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, India, Malaysia, Mongolia, Dubai (UAE), Japan, South Korea, Nepal, The Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Italy, Germany, Bangladesh, Australia, United States, and United Kingdom and Ireland.

For a complimentary subscription to China Briefing’s content products, please click here. For support with establishing a business in China or for assistance in analyzing and entering markets, please contact the firm at china@dezshira.com or visit our website at www.dezshira.com.

- Previous Article Hong Kong IRD Warns Public About Fraudulent Stamp Duty Certificate Notices

- Next Article