China Taxes, How Do They Stack Up Against Emerging Asia?

Op-Ed Commentary: Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Oct. 20 – I’ve just been presenting on the tax regime throughout Asia at the CCH annual China Tax Conference being held in Shanghai. It’s the first time this event has been held in China and the response has been overwhelming. My function has been to provide an overview of the changing tax regime across Asia – a huge subject, but one that holds a great deal of interest.

Suffice to say, Asia’s tax regimes are changing fast, and it’s important to keep abreast about what is happening and where. Times are tight, and pencil sharpening, together with increasing interest in the use of special purpose vehicles, tax havens, and the application of double tax treaties are gathering ever more scrutiny from various Asian governments, and China in particular.

There are also significant tax reforms on the immediate horizon, not least with India, which is about to completely reform its entire tax code. Corporate tax in India is about to significantly drop in early 2011, while countries such as Vietnam have also undergone radical reforms. It’s not just a huge subject; it’s also immensely complicated and very much a moving target.

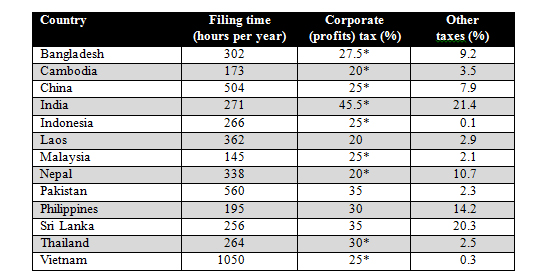

But to provide something for China Briefing readers as a take home from this, it’s worthwhile to take a snapshot of where China is right now and how it stacks up against the rest of Asia. The chart below is simple, and deals from left to right with the World Bank assessments of how many hours it takes in each country to file various mandatory tax forms. That’s useful as a pointer to two elements; firstly how archaic the system is (such as Pakistan) or secondly, how much increased attention to detail is now being required as governments clamp down and insist on increasing amounts of data (such as China).

The corporate tax rates apply as of today, but please note the addendum below, especially concerning India.

Finally, “other taxes” refers to the combined smaller taxes that also bite into profitability (China for example has an additional nine taxes that can impact corporate performance in the country: resource tax, land appreciation tax, real estate tax, vehicle and vessel tax, stamp duty, deed tax, customs duty, urban land use tax, and farmland use tax). The figure adds these up in each country and breaks them down into averages.

The comparison makes for fascinating reading:

*Notes

- In Bangladesh, a 27.5 percent corporate tax rate applies to publicly traded companies; a 37.5 corporate tax rate applies to non-publicly traded ones.

- In Cambodia, companies involved in oil and gas, and certain mineral exploitation activities are subject to a 30 percent corporate tax rate.

- In China, the standard corporate income tax rate in China is 25 percent. A special tax rate of 20 percent applies to small-scale enterprises; also a special 15 percent tax rate applies to state-encouraged new high-technology enterprises.

- In India, foreign companies are subject to a 45.5 percent corporate tax rate, while a 43 percent corporate tax rate applies to domestic firms and companies. However this is due to change with tax reform due next year which when passed will reduce the CIT rate to 30 percent flat, and “Other Taxes” to about 12 percent.

- In Malaysia, SMEs (Shares of RM.2.5 million and below) are subject to a different tax: the first RM500,000 of chargeable income of a SME is taxed at 20 percent, with the balance being taxed at 25 percent.

- In Nepal, companies involved in tobacco, bidi, khainy, alcohol and beer are subject to a different corporate tax rate of 25 percent.

- In Thailand, there are several tax rates for companies of different sizes. Companies whose net profit does not exceed Baht 0.15m are exempt; net profit over Baht 0.15m but not exceeding Baht 1m: 15 percent; net profit over Baht 1m but not exceeding Baht 3m: 25 percent; net profit exceeding Baht 3m: 30 percent.

- In Vietnam, businesses engaged in prospecting, exploration and mining of petroleum, gas and other rare and precious natural resources are subject to corporate rates from 32 to 50 percent.

The literal elephant in the room here is indeed India, whose reforms will have a major – and positive – impact on the amount of tax foreign investors need to pay. Essentially, what India is doing with reform is to widen the tax net to have more contributions, yet reduce it at the top end. Consequently more Indians will pay tax, but the corporate tax rate and additional taxes are set to drop substantially. This will have a major impact on FDI into India when these reforms are passed early next year.

However, such comparisons still do not tell the whole story. What isn’t included here for example are the immensely varying forms of labor related costs – which in China add up to about 40 percent of each employee’s salary – paid by the employer. In India, such amounts typically are around 10 percent. China’s may also increase. An aging workforce may mean an additional percentage point being added on here and there for increases in pensions and medical insurance. These variations make a huge difference when calculating comparisons and overhead liabilities.

Individual income tax can also become part of a corporate liability in terms of having certain mandatory corporate payments being linked to the employee salary. Plus IIT itself varies tremendously across the region. In China the top range is at 45 percent, in India it is about to become 30 percent, and in Vietnam it is 35 per cent. Again, comparisons need to be made. How much money can be put into employees pockets and at what cost to the company is a key issue for attracting and retaining quality staff. Some tax regimes are rather more attractive at this than others.

VAT is another issue that can greatly impact upon performance. All countries tend to adopt a band of VAT for varying products, yet with one prominent “catch all” rate that applies to most products. In China that is generally 17 percent, In India what will become goods and service tax (GST) is expected to be about the same, while in Vietnam, the general rate is 10 percent. Countries also are getting smarter at applying taxes to either punish or to encourage specific industries. Export duties in Vietnam for example are only levied on a very few products, for pretty much everything else it’s zero rated. That’s a great deal, and demonstrates the increasing desire of the Vietnamese to compete with neighboring China for part of its export manufacturing industry. Vietnam also becomes attractive when considering dividends tax – it levies zero, while for India levies 15 percent and China 10 percent.

The latter tax however is also influenced by double tax treaty agreements. China’s DTA with Singapore for example reduces that specific burden by half. Indeed, all of the countries featured have extensive – and growing – DTA agreements and these can impact greatly upon profitability and even where to locate a physical presence in Asia.

China actually comes out of the direct tax comparison rather well, the trick however when assessing the true China cost is to factor in welfare payments, which are a direct cost, and dividend taxes, which may be offset in full or in part by a DTA. The extent of VAT and how much is reclaimable is also a variable that should be calculated.

While the table above may be a useful starting point, tax planning in China and Asia is a complex affair, and attention to detail needs to be put into place. In essence then, the boxes to check when assessing the complexities of tax comparisons are as follows:

- What are the current direct taxes applicable?

- What are the current indirect taxes applicable (stamp duties, customs duties, land use etc.)?

- Are these to be subject to major reform in the short term (such as India)?

- What are the individual income tax rates and how does this impact?

- What are the labor costs in terms of mandatory payments (pensions, unemployment, insurance etc., usually calculated as a percentage of salary)?

- What is the VAT rate and how much is reclaimable upon export?

- Does any withholding tax apply if trading from overseas?

- Are there dividend taxes due upon repatriation?

- What DTA can be utilized to offset some of the liabilities?

As Asia becomes increasingly attractive for foreign investors, and indeed for the shifting of some industry around the region, these issues need to be addressed. Governments throughout the region are waxing and waning between tax friendliness and increasing scrutiny, and investors involved in the region should take stock, make use of the check list, and above all refer to sound professional advice with multi-jurisdictional expertise to assess the optimum solution to the tax questions that arise when considering investment into China, India, Vietnam or anywhere else in emerging Asia.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the principal and founding partner of Dezan Shira & Associates, establishing the firm’s China practice in 1992. The firm now has 10 offices in China. For advice over China strategy, trade, investment, legal and tax matters please contact the firm at info@dezshira.com. The firm’s brochure may be downloaded here. Chris also contributes to India Briefing, Vietnam Briefing, Asia Briefing and 2point6billion.com.

The practice also provides a series of foreign direct investment publications concerning China, India and Vietnam, and specific tax detail on each through a subsidiary publishing house. Please visit the Asia Briefing Bookstore to browse regional magazines and books as pertinent.

Related Reading

![]() The Asia Comparator

The Asia Comparator

(14 Asian cities prices, costs and wages examined and compared – US$10)

![]() China-India Investment, Tax and Trade Comparison

China-India Investment, Tax and Trade Comparison

(complimentary download)

(fourth edition, updated for 2010 – US$25 hard copy; US$40 PDF)

New India Tax Code to Provide Incentives for Investment

India to Keep SEZ Tax Exemptions Until 2014

- Previous Article CCH Asia Tax Summit 2010 – Shanghai

- Next Article China WFOEs: It’s Not Standard Law, It’s Getting the Finance and Tax Right