China’s City-Tier Classification: How Does it Work?

China’s city-tier classification is popularly used by businesses to guide their market entry strategy. China Briefing explores the criteria defining the respective city-tiers and their utility to determine whether the system is an effective and relevant tool for investors.

A common mistake made by foreign investors entering China is to approach the country as a single, unified market. In reality, the Chinese market is of enormous size, scale, and diversity.

To give an example of this, the country is home to some of the wealthiest cities in the world, such as Shanghai, which records a population equal to that of Australia at about 24 million people, and a GDP that rivals the Philippines at US$469 billion.

China is also home to much smaller, lesser-known cities like Gannan in the north-central province of Gansu, with a population of 710,000 whose GDP recorded in 2016 was US$2 billion. In 2016, Shanghai’s GDP per capita income was over US$17,000 and Gannan’s was about US$2,876.

Consequently, the city-tier classification system offers foreign investors a practical tool to navigate the 613 (officially recorded) cities that make up China. Businesses use the tier categorization to track city development, market trends, and tax policies and incentives, among other things.

However, despite the popularity of the city-tier system, little is known about the precise criteria that determine the classification of a city in a specific tier. In this article, we briefly examine the parameters often cited as defining the scope of China’s respective city-tiers and assess their utility and limitations.

What is the city-tier classification system?

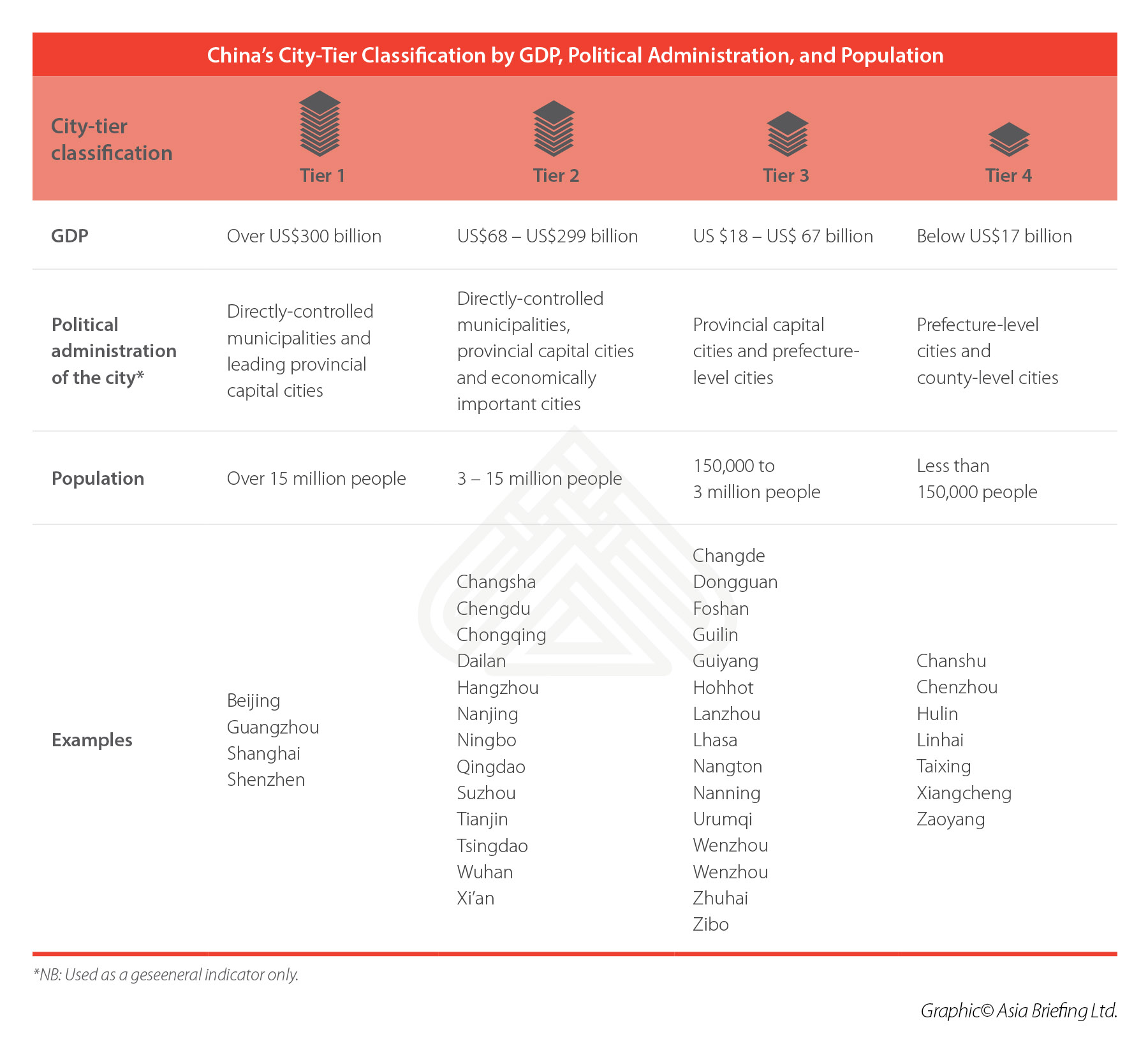

The most common system of ranking Chinese cities is to categorize them into four respective tiers.

Traditionally, Tier 1 cities are the largest and wealthiest – often considered the megapolises of China. As the tiers progress, the cities decrease in size, affluence, and move further away from prime locations.

However, growing regional disparity in China has created a greater need for city-by-city distinction, leading to the emergence of lower-tier categories.

Depending on whom or which organization you ask, there are now six, eight, 14, or even 18 city-tier categories in China. Half-rankings (such as ‘Tier 1.5 or 2.5’) have also become increasingly common, particularly in the real estate market.

Most commonly, cities referred to as ‘Tier 1.5’ or ‘emerging first tier’ cities represent those that do not equal the traditional first tier cities, such as Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen but stand out beyond other traditional Tier 2 cities.

Defining the criteria

In contrast to China’s city clusters – which groups cities by geography, economic, and trade links – professional opinion continues to differ on what parameters are used to define each city-tier.

According to the SCMP exclusive on city-tiers, most factors used to define city-tiers fall within three macroeconomic categories: GDP, population, and politics. The cities are then allocated a tier – based on the average of these three factors.

The SCMP criteria resulted in: five Tier 1 cities, 30 Tier 2 cities, 138 Tier 3 cities and 480 Tier 4 cities.

More recently, Chinese news source, Yicai Global, released their own formula in the report “2017 China City Business Charm Ranking”, categorizing Chinese cities into six tiers using the five measures below:

- Concentration of commercial resources;

- City’s pivotability;

- Citizen vitality;

- Lifestyle diversity; and

- Flexibility in the future.

The Yicai classification resulted in: four Tier 1 cities, 15 emerging Tier 1 cities, 30 Tier 2 cities, 70 Tier 3 cities, 90 Tier 4 cities and 129 Tier 5 cites.

However, indicators such as ‘variety of lifestyle’ and ‘flexibility in the future’ have been criticized as being vague and hard to quantify.

More novel indicators include measuring the presence of prominent Western brands, such as using the number of Starbucks stores to distinguish between a Tier 2 city and a Tier 3 city.

Market potential of lower-tier cities

The city-tier system is a simple way for foreign investors to gain a birds’ eye view of the myriad of markets that make up China. It can be used by investors to inform their market entry decision or to guide their expansion plans.

“Companies may turn to the city-tier system to gain a preliminary understanding of which cities best fit their business plans as major operational costs, such as wages and rent, tend to be co-related with a city’s classification,” Thibaut Minot, Assistant Manager at Dezan Shira & Associates’ International Business Advisory department explains.

“For example, a manufacturing company may choose to locate themselves in a lower-tier city in order to capitalize on lower operational, land, and labor costs, or may choose a top-tier city for the quality of labor and local infrastructure that it has to offer.”

In addition, the tier system can help brands understand the consumer dynamics of a particular city, before positioning themselves in a location most suitable for their business.

Andrew Cameron, Senior Client Manager at The Silk Initiative explains that “A coffee brand in a Tier 1 city like Shanghai does not need to sell the idea of a coffee shop to consumers, as there is already a Starbucks store at every corner of the city. However, the same coffee shop entering a lower-tier city such as Urumqi, may be required to sell the product and the experience of consuming coffee, as well as the brand itself.”

Foreign investors can also use the categories to unlock opportunities in lower and emerging tier cities that often go overlooked but will assume a larger proportion of the affluent middle class in the coming years.

According to data published by Morgan Stanley, the spending power of consumers residing in China’s lower-tier cities is expected to grow to US$6.9 trillion in 2030.

“I see time and time again how understanding the different tiers in China can aid brands in devising an appropriate business strategy,” Cameron comments.

He explains further using the example of Danish brewing company Tuborg’s initial China strategy.

“Initially Tuborg was to enter into Tier 1 cities, much like its parent-company Carlsberg. However, they were ultimately unsuccessful as the market was saturated with too many competitors – including its own partner company. Tuborg eventually went on to relaunch in Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities, becoming one of the early players in the lower-tier markets. Here they teamed up with music festivals and other events to tap into the local culture, allowing Tuborg to play a strategic role within the portfolio.”

Ultimately a guide, not an exhaustive tool

China’s city-tier classification continues to be a good reference point for businesses seeking a general overview of the Chinese market. However, the system is by no means comprehensive and should not be used in isolation.

As Cameron puts it in the context of the F&B industry, “Having worked closely with many food and hospitality brands, the most crucial thing to take into account is the differences in local culture and taste preferences, which fall outside of what the city-tiers are able to measure.”

An additional problem is that in opting for a ‘best fit’ assessment when assigning city-tier categories, the classification may overlook other unique socioeconomic, geographic, and cultural factors. This could be consumer behavior, per capita disposable incomes, exposure to international trends, and cultural preferences.

Indeed, a city can be first tier in terms of GDP and infrastructure but may have the consumer mindset more similar to third or fourth-tier cities – a factor that could lead to the success or failure of a brand.

Despite this, firms can still leverage the information derived from the city-tier classification to gain a quick overview of which cities will favor their business goals and brand marketability.

About Us

China Briefing is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists foreign investors throughout Asia from offices across the world, including in Dalian, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. Readers may write china@dezshira.com for more support on doing business in China.

- Previous Article Relations Chine-Sénégal en 2019 : Vers un partenariat commercial plus fécond ?

- Next Article China’s Two Sessions 2019: What to Expect