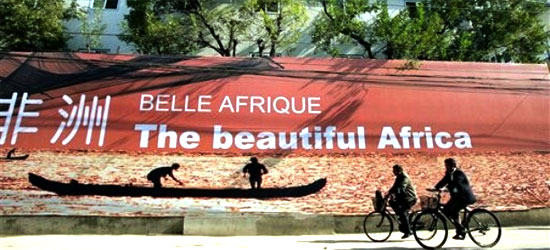

China’s Africa Strategy Blossoms as Relationship Develops

AP PHOTO

By Chris Devonshire-Ellis

NAIROBI, Jun. 8 -China has stepped up its foreign policy of friendship and trade with Africa this year as it seeks to further strengthen its ties throughout the continent. With President Hu Jintao having already visited Mali, Senegal, Tanzania and Mauritius, China announced a new Beijing summit of African nations aimed at actively developing a strategic China-African partnership. Chinese influence pan-Africa, unencumbered by colonial history, the politics of aid, and an understanding of how sometime dictatorial governments work, is set to rise significantly across the region.

Hu’s visit, coming as it did during the shock waves of the global financial crisis, appears structured to convince African nations that China intends to be rather more than a fair-weather friend. With Africa having been apparently placed at the bottom of the pile of importance by economically battered European nations, China has been quick to assert itself in their absence. Accusations that China has cherry-picked African nations for strategic alliances appear to have been reversed. None of the four nations visited are particularly rich in resources. That means hats off to China’s foreign policy and strategy in Africa, recognizing that rather than national borders, Africa remains, despite previous colonial attempts to draw lines, largely a tribal continent. Doing business based purely on Africa’s national borders and localized mineral or resource wealth doesn’t necessarily cut it. China’s strategy of dealing with Africa carefully, but as a whole, appears to be paying dividends that the previous colonial powers just cannot match due to their inherent historical bias.

China has also uncovered a powerful windfall in its acquisition through trade of trillions of U.S. dollars. While to the West, the appreciation of the dollar has been hurting large sectors of the U.S. economy, for China, away from the prying eyes of Washington, it means both China and several other Asian countries – such as India and Thailand – have acquired significant purchasing power in world markets. Additionally, oil and other commodities have been at their lowest levels for several years, resulting in China finding itself in a powerful bargaining position in what has become a global buyers market to those nations who have the cash. China is signing long-term deals with many African nations for a variety of natural resources. When the global recovery comes, as one day it must, China will find itself in control of considerable portions of the world’s natural resources, including oil. Africa therefore now finds itself in the rare position of being courted by the United States, the EU and Asia; with China currently the top player.

African trade is also changing. Asia is now developing and is likely to become Africa’s largest bloc trading partner within the next decade, a complete turnaround from twenty years ago when African-Asian trade barely registered. This may represent more of a return to the norm than is generally recognized. History shows us that Africa was plugged into the ancient Silk Road, with sub-routes running from Ghana (gold) through North Africa and joining the silks and other commodities passing to and from China in the Middle East or at Istanbul. Indeed, a trip to the Silk Road Museum in Urumqi, Xinjiang a few years ago with a Kenyan friend of mine, proved the point. Dug up from the sands of the Taklimakan Desert was a medium sized pot, with quite distinctive markings. Labeled “origin unknown” by the museum’s curators, my colleague immediately identified it as coming from a specific African coastal region, close to what is now Mombasa. The markings, he said, were quite unmistakable as being from a particular African tribe who still use the same patterns today.

Africa’s position however has altered. The phrase “white elephant,” meaning a grand project of little use, actually originated as a direct result of European colonialism in Africa. With part of the Cold War being played out in Africa, both the West and the Soviet Union installed puppet dictators and lent money. With political support guaranteed, such a system resulted in grandiose projects that made contractors wealthy, while much of the cash went to banks, re-lending it at exorbitant rates. The prices of exported commodities were kept low, while manufactured goods became expensive. African countries became burdened with spiraling debt just as their export markets were booming.

This situation has only recently been turned around by the arrival of the Asian Tigers in Africa’s recent economic history. Exporting aggressively, and undercutting traditional, mainly European producers, Asia rapidly began to view Africa as both a large potential export market but also as a source of resources. In some cases, however, Africa still has to learn to insist on quality control measures. As China politically strengthens its position in Africa, many low-end Chinese exports are just not up to standard and the country is generating a reputation for poor quality goods. Friends of mine reference a Chinese made hammer, which after just six blows to knock a wooden peg in the ground to secure a safari camp tent, broke in several pieces – the wooden handle cleaving in two and the metal head fracturing into pieces. I have heard recurring stories across Africa of similar incidents involving cheap Chinese products; the dumping perhaps of shoddy goods long discarded by more sophisticated markets? China still has a large number of low-level, poor quality-producing state-owned enterprises to maintain for the sake of its workers, and it wouldn’t surprise me if such products are now being sent to Africa, where corruption, a lack of QC supervision on imports, and possible political pressure allow such product entry.

Regardless, trade volumes between Africa and Asia have sky-rocketed. Exports from Africa grew annually at 15 percent from 1990 to 1995, and has reached 20 percent plus for each of the past twelve years. African trade with China alone in 2008 was US$106.84billion, up 45 percent over 2007. At present, African trade with Asia is running at about 30 percent of that which it enjoys with the EU and the United States, however, the volume of trade has grown exponentially partly due to improvements in infrastructure and the proximity of the two continents. It takes just five hours to fly from Nairobi in Kenya across the Indian Ocean to Mumbai – the same time it takes to fly from Urumqi to Beijing.

Currently, just five African nations account for 85 percent of all Asian trade, however, with infrastructure developments and political reform occurring in Africa too, bottlenecks that have traditionally gotten in the way of such commerce are gradually – and in several cases quickly – being removed. Asian demand for finished product from Africa is increasing, and has been growing at about 20 percent per year, particularly in textiles and apparel. African imports on the other hand include machinery and equipment, vehicles (including Indian and Chinese made motorbikes and trucks), and electronic goods and appliances. Beijing has encouraged this trade by removing or reducing tariffs on a wide variety of African imports and has signaled it may do so again to further boost trade.

China’s long arm of commerce therefore is moving steadily and strongly to Africa. It is time to take heed.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the founder of Dezan Shira & Associates, an FDI consultancy that has helped structure Sino-Africa joint ventures on the mainland. He spent 21 years in China and now heads up the firm’s operations in India.

Further Reading:

China and Africa: A three part series that examines China’s emerging relationship with Africa – from oil and aid to soft diplomacy and African investment on the mainland.

- Previous Article Gov’t Wants Censor Software on All PCs Sold in China

- Next Article China Eastern, Shanghai Air to Merge