Getting Growth Into Asia – The India Option

As we are now in the midst of a China slowdown expected to last a minimum of two-three years, in this series of articles I have been looking at China alternatives when it comes to getting growth into your Asian business. As I discussed in an earlier article, my view is that China’s GDP growth is probably at about the three percent mark nationally, with some provinces almost certainly experiencing lower and even negative growth.

![]() RELATED: Getting Growth Into Asia – the ASEAN Option

RELATED: Getting Growth Into Asia – the ASEAN Option

Growth dynamics in Asia are still very much a regional, rather than national, issue. In China, the north-east has particular problems, yet in Guangdong the going is still good. Relatively high GDP growth can also mask a series of serious underlying problems – as is the case in ASEAN. Myanmar, for example, has growth of six percent, but this is unfortunately not matched by its human capital value, which remains extremely low. Growth may exist, but most of the working population remain subsistence farmers. Putting them to work in a factory requires extensive investment and training. Meanwhile, nearby Vietnam is booming in terms of foreign investment

Evaluating growth and where your best options lie, then, is a skill that requires regional research, experience and understanding. Nowhere is that more true than in India.

For the past two years, India’s GDP growth rates have overtaken those of China, and look set to stay that way for the indefinite future. The main reason for this is the worker demographic dividend, which India is in the process of inheriting from China. Simply put, India has a workforce of about 450 million, with an average age of 23. That workforce is also growing each year – India doesn’t have any one-child policy as China had implemented. This is manifesting itself as an inexpensive, yet young and hard-working worker base unmatched by anywhere else worldwide.

China in comparison has just slightly less than 900 million workers – double that of India at present. However the China trap is that this worker population is significantly older, with an average age of 37. That is making them far more expensive – China has raised its minimum wage by an average of 18 percent per year, each year for the past six years. China is also now losing workers from its workpool as they become older and retire. Additionally, the overall employment cost in China is far higher than India. China mandatory welfare payments work out at an average of 35-40 percent of salary; in India, is it an average of 5 percent. The upshot of all this is that the total average labor cost in India is 20 percent of a Chinese factory worker. Not surprisingly, this is now having an impact on where large workforces are located.

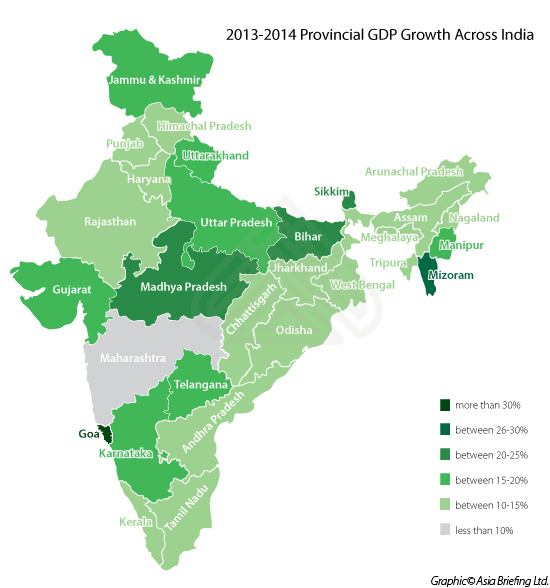

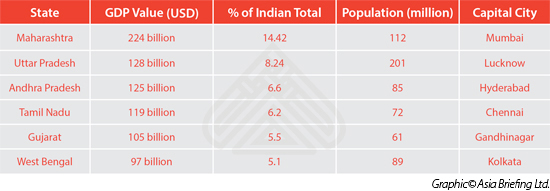

However, the map above, although impressive, is somewhat misleading when taken at face value. Although much of the country is steaming ahead at growth rates in excess of 20 percent, care needs to be taken as some of the Indian states are developing from a very low economic base. In fact Maharashtra, the lowest performing state in terms of growth (2015: 7.4 percent) actually contributes a massive 14.42 percent of the entire national GDP of USD1.9 trillion. Home to the major port city of Mumbai, Maharashtra is by far and away India’s wealthiest state, and Mumbai its wealthiest city. Those lower growth rates are, in Maharashtra’s case, indicative of an already developed economy. Other Indian States to look at include:

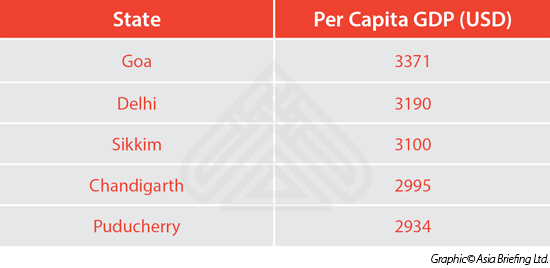

In terms of per capita Income, India still has a tremendous gap between the rich and poor. This manifests itself throughout its cities and across its states, where beggars sit cheek by jowl with millionaires. This economic disparity is rooted in ancient Hindu and Buddhist beliefs of re-incarnated karma and the caste system, despite government attempts to stop it and spread wealth more evenly. At present Indian society is ill-disposed to accept change in this regard.

China in fact had very similar problems, with the CCP only recently putting a stop to it via violent social upheavals and the forced re-possession and redistribution of wealth. It is unlikely that democratic India will take this path. Mumbai meanwhile, despite being India’s wealthiest city, ranks low in overall GDP per capita due to its attracting millions of very low paid migrant workers, many from West Bengal. This pushes down Mumbai’s GDP per capita to just over US$2,000, although it isn’t necessarily representative of the overall wealth of the average middle class citizen born, educated and working in the city.

India’s highest GDP per capita can be found in the following states:

These figures demonstrate the complexity of the Indian market. Cities and even states may be relatively wealthy, yet the GDP per capita average may not reflect this. This means market research is required to drill deeper into the Indian market in order to fully understand where the opportunities lie. Overall, though, it pays to remember that India is currently the world’s ninth largest economy, and third in purchasing parity terms after China and the United States. There is considerable wealth in India.

In terms of selling to other markets, India has a similar advantage to China in that it also has signed off a Free Trade Agreement with ASEAN. It is arguably more expansive than China’s deal as, in line with India’s service economy, it contains far more provisions for intra-ASEAN-India services than the ASEAN-China agreement. This means that taking advantage of India’s English speaking and well educated middle class population, housing them in back offices in India and putting them to work on R&D and other service industries which target the Asian consumer is a sound strategy. It should also be pointed out that Indian investors setting up subsidiary operations in ASEAN can also then take advantage of the ASEAN-China FTA and sell to the Chinese market at the reduced tariffs under that agreement. With those lower wage levels in both India and the ASEAN economies such as Vietnam, getting goods of ultimately Indian beneficial ownership onto the ASEAN and China markets has never been easier.

India is going through a period of reforms and, for the first time in over 20 years, has a business and investment minded, democratically elected government in place with an absolute majority in Parliament. This means Prime Minister Modi – who previously oversaw a decade of 10 percent plus growth as governor of his home state of Gujarat – is finally able to get much-needed reforms into the Indian system. This includes an overhaul of the tax system, and a better concentration on regional Free Trade Agreements. To date, India has been somewhat late in getting these into place, and with the exception of the ASEAN-India FTA, only has a limited number of other FTAs. This appears likely to change, however, and the government has expressed a desire to fast track negotiations with other countries, including the European Union, Canada and Peru .

India is involved in discussions concerning the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) which includes China, the ten ASEAN nations, Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand. Considered by some a counter-weight to the new TPP agreement, the prospect of a Free Trade deal that includes China and India is enticing. In fact, although the current headlines are all about the TPP, the RCEP’s potential is currently being studied by Beijing at the request of APEC. The report on that should be due and presented to APEC members late next year. If positive, we may see either the rapid conclusion of a RCEP agreement or a deal to merge it with the TPP. The implications for either scenario are positive for India. Nothing happening would be damaging.

In summary, India represents a potentially alluring prospect for foreign investment. Money is there – it has a wealthy middle class consumer base of 250 million, and Hermes and Ferrari outlets amongst other premium brands already exist. Some of India’s largest private sector companies, such as Tata, Infosys and Reliance are world class in a manner in which the Chinese SOEs can only dream about.

Getting India right, however, is a time consuming process that requires much research. The rewards are potentially there. The trick is a matter of timing – if the RCEP and EU Free Trade deals can be pushed through, then it makes sense to be in the country now to start learning. India therefore remains largely unknown and unproven. But if the government’s reforms and trade deals can successfully be pushed through, India could become the new Workshop of the World.

|

Chris can be followed on Twitter at @CDE_Asia. Stay up to date with the latest business and investment trends in Asia by subscribing to our complimentary update service featuring news, commentary and regulatory insight.

|

![]()

An Introduction to Doing Business in India 2015 (Second Edition)

An Introduction to Doing Business in India 2015 (Second Edition)

Doing Business in India 2015 is designed to introduce the fundamentals of investing in India. As such, this comprehensive guide is ideal not only for businesses looking to enter the Indian market, but also for companies who already have a presence here and want to keep up-to-date with the most recent and relevant policy changes. We discuss a range of pertinent issues for foreign businesses, including India’s most recent FDI caps and restrictions, the key taxes applicable to foreign companies, how to conduct a successful audit, and the procedures for obtaining an employment visa.

Importing and Exporting in India

Importing and Exporting in India

In this issue of India Briefing Magazine, we examine India’s import and export landscape, basic import and export procedures, as well as the customs duties. We note that India’s import-export landscape has remained stable despite significant economic changes. This bodes well for businesses that trade with India.

How to Establish a Business in India

How to Establish a Business in India

In this issue of India Briefing Magazine, we explore market entry options that allow foreign investors to test the water before diving into the Indian market. We examine the government’s new eBiz portal, provide a step-by-step guide for setting up a liaison office (LO) in India, and finally conclude by examining the strengths and weaknesses of India’s LOs.

- Previous Article How U.S. Companies Can Access the ASEAN, Chinese & Indian Domestic Markets Via the TPP Agreement

- Next Article China Plus One – Where Foreign Investors Are Really Heading in Asia